With a major Robert Rauschenberg retrospective opening at Tate Modern in December, Alex Needham, writing for The Guardian, visits the late artist’s island home of Captiva, Florida:

Rauschenberg started visiting in 1962, before moving to Captiva nine years later, describing it as “the foundation of my life and my work… the source and reserve of my energies”. His work by then had become ambitious and complicated; Captiva forced a return to simplicity, and the first things he produced were a selection of wall sculptures made from battered cardboard boxes.

For the world beyond Captiva’s white sands, however, a reacquaintance with Robert Rauschenberg is long overdue. In Britain, there has been no major retrospective of his work since 1981, while the last big US survey, at the Guggenheim in New York, took place in 1997. That will change next month, when Tate Modern opens a London retrospective; it will then move to Moma in New York next May, and after that to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Rauschenberg left a bold and indelible mark on the 20th century. His combines, which integrated the flotsam and trash of everyday life, including the artist’s own duvet in Bed (1955), were neither painting nor sculpture, and proved that anything could be the material of art. At Tate Modern, pride of place will be given to Monogram 1955–59, a horizontal canvas on which perches a stuffed goat with a tyre around its midriff; the work thrilled and scandalised when it was first shown at Castelli’s gallery in New York, and rapidly became synonymous with the artist’s iconoclasm. Since then, his relevance has only increased, says Leah Dickerman, co-curator of the new retrospective: “When you open a gallery and see the art that’s made out of the stuff of the real world, that’s coming off the walls, that’s interdisciplinary in its approach, all that is the legacy of Rauschenberg.”

Also at writing for The Guardian, Olivia Laing, author of The Lonely City and The Trip to Echo Spring, looks back over Rauschenberg’s career:

Making the combines, Rauschenberg felt he was cracking “the secret language of junk”. They could be composed of anything: a goat corseted by a tire; a stuffed bald eagle. One of the very first, Untitled (Man with White Shoes), contained – deep breath – fabric, newspaper, a photograph of Jasper Johns, a handwritten letter from Rauschenberg’s son, a drawing by Twombly, glass, mirror, tin, cork, a pair of the artist’s socks and painted leather shoes, dried grass and a taxidermied Plymouth Rock hen.

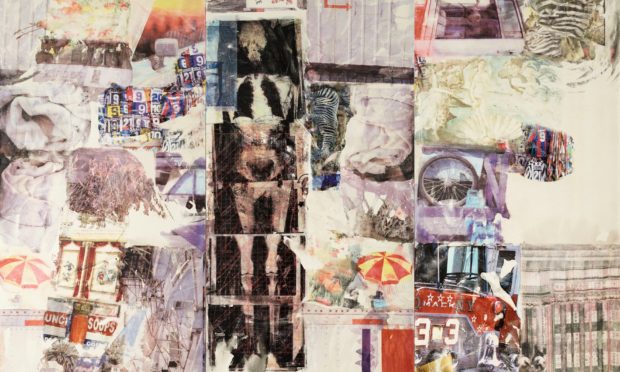

All the same, there’s a limit to how much world you can cram into a sculpture, and as Rauschenberg’s success grew he became increasingly fascinated by replication. Back in 1952, he’d experimented with transfer drawing, and in 1958 he embarked on a grand project of illustrating Dante’s Inferno using lighter fluid to transfer images on to paper. In 1962, Andy Warhol introduced him to a far more sophisticated technique: the wizardry of using photographic images on silkscreen canvases.

Now he could reuse and resize his own photos and those he snipped from newspapers and magazines, giving him an unprecedented power of composition. Anything could be incorporated: John F Kennedy; a water tower; Bonnie and Clyde. As he gleefully observed of the silkscreen paintings: “It’s as much like Christmas to me as using objects I pick up on the street.” He was giddy for them, until in 1964 he was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. Terrified of stasis, the next day he called his New York studio and asked his assistant to burn all the screens.

See also: Hal Foster on Rauschenberg retrospective for the London Review of Books,