The New Yorker visits the Community Bookstore in Brooklyn as owner John Scioli begins to clean out his “cavern of books” in preparation of the store’s closing in May:

Comments closedTag: New York

From Thomas Mann to Amazon — The Art of Literary Publishing in New York

The Millions has a long, but very interesting (and, at times, surprisingly blunt) essay by veteran Doubleday editor Gerald Howard on editing and literary publishing in New York:

At the simplest, most basic level, I’ve been reading for a living for 37 years. I arrived at New American Library with a literary and intellectual sensibility formed by the unruly rebellions of the ’60s and the spiritual deflations of the ’70s, with a taste for the novelists and thinkers who had either helped to cause or best reflected and interpreted those rebellions and deflations. I’ve read thousands of books and proposals since then, and I believe I am a better reader than I was at age 27 — I know more because I’ve read more and my judgments are (I sure hope) better informed and more mature. But at the primal level where reader meets text and experiences emotions ranging from boredom and impatience to I-love-this-and-have-to-have-to-publish-it excitement, I think I am still that young man in the hunt and on the make, always searching for the big wow. This process takes place in the private arena of the mind and is entirely unrelated to the corporate arrangements of my employer. It is, quite literally, where I live, where I feel I am most myself.

As for the editing of those books that wow me when happy circumstances dictate that I get to acquire them, that process too takes place in a private arena. When I encounter a sentence that is inelegant or ungrammatical or inefficient or ambiguous in meaning, or a scene in a novel that is implausible or overdone or superfluous, or a plot that drags or goes off course or beggars credulity, or a line of exposition that falls short of the necessary clarity, or feel that some subject is missing and requires coverage, I point those things out to the author and with a carefully calculated mixture of firmness and solicitude suggest ways they might be remedied. I do this usually at nights and on weekends, sometimes on my bus ride to and from work, very occasionally in my office on slow days with my door closed (yes, I have an office with a door that closes), with a complete absence of business calculation beyond the largest context — that a book that is bad or just not good enough is a book that will embarrass me and my employer and be poorly received and will not sell.

But as I read those submissions and edit those manuscripts, on another cognitive plane I am reality testing what I am reading. What other books — the fabled and often tiresome “comp titles” — are like this one, and how did those books sell? (We are always fighting the last war.) Is it too similar to something we published recently or are publishing in the near future, or to a book some other house has or shortly will publish? Are there visual images in the book that might be utilized on the cover? What writers of note can I bug for prepublication blurbs? Is there something about the author, some intriguing or unusual backstory, some charisma radiating off the page (and maybe the author photo? Don’t act so shocked) that suggests that he or she will be a publicity asset? What might a reasonable advance be, given the amounts that have been paid recently for similar books, or might reason for some reason be thrown out the window? (A friend and colleague of mine refers to this feeling as “Let’s get stupid.” More on this matter shortly.) What colleagues in the company, in the editorial department, in marketing, publicity, and sales, could I ask to read the book to drum up support for it? What is my “handle” going to be — the phrases or brief sentences that briskly encapsulate a book’s subject matter and commercial appeal? These and all sorts of other questions will be popping up in my brain, and inevitably there is some crosstalk and bleed-through between the two cognitive spheres. If you want total purity in these matters, go join an Irish monastery and work on illuminated manuscripts, not a New York publishing house. Or at the very least a quiet and scholarly and well-endowed university press.

Well worth reading from beginning to end, the essay is an excerpt from the forthcoming Literary Publishing in the Twenty-First Century edited by Travis Kurowski, Wayne Miller, and Kevin Prufer (to be published by Milkweed Editions in April 2016), which on this evidence of this alone will be essential reading for publishing folks1.

Why McNally Jackson Books Thrives

The New York Business Journal looks why McNally Jackson is thriving, while other the city’s other independent bookstores are disappearing:

most literati agree that independent book stores are an endangered species in high-rent New York. See what’s happening right now with the St. Mark’s Bookshop, which was forced to move once and now is preparing to close for good. Or look at what’s already happened to Gotham Book Mart, Biography Bookshop, Bank Street Bookshop and even the chain store Borders Books. All are shuttered. Even Barnes & Noble has closed three large outlets in Manhattan (Astor Place, Chelsea, Lincoln Center).

But something special is brewing on Prince Street in NoLita because McNally Jackson is packed. The café is booming, the self-publishing arm is prospering, and the nightly literary events, are popular. McNally Jackson is the prime example of what it takes for an independent bookstore to succeed: operating as a triple threat of bookstore, café and publisher.

Comments closed

Gramercy Typewriter — Family Business Since 1932

The latest short film in Huck magazine’s ‘Family Business’ series visits Gramercy Typewriter Co., the father and son typewriter repair shop in New York:

You may remember that Gramercy Typewriter Co. was the subject of another short documentary a couple of years ago…

(via It’s Nice That)

Comments closedChris Jackson: Building a Literary Movement

New York Times Vinson Cunningham profiles Chris Jackson, executive editor at Spiegel & Grau and editor of award-winning author Ta-Nehisi Coates:

Comments closedJackson’s role… is to perform nothing less than a kind of magic. He stands between the largely white culture-making machinery and artists writing from the margins of society, as well as between the work of those writers and the largely white critical apparatus that dictates their success, in both cases saying: This, believe it or not, is something you need to hear.

The book that perhaps best encapsulates that ethos is one of Jackson’s first, ‘‘Step Into a World: A Global Anthology of the New Black Literature,’’ published in 2000. The collection, which he and the ‘‘Real World’’ star turned hip-hop journalist Kevin Powell compiled, brought together a cohort of writers — Junot Díaz, Edwidge Danticat, Paul Beatty, Hilton Als, Claudia Rankine and others — who have today come to form a loosely generational, unabashedly multicultural alternate literary establishment. ‘‘Step Into a World’’ marked a turning point for Jackson, who had until then been publishing reference works that were the stock in trade of John Wiley & Sons, where he worked at the time.

‘‘I’ll never forget a reading we did for that book,’’ he told me. ‘‘It was at the Schomburg’’ — the Harlem library that is a repository of black literature and history — ‘‘and there were so many people there, not just publishing people, as we usually think of them, but people from the neighborhood, and they were picking up this book.’’ He paused here, after uttering the word book, and his abiding wonder at the power of the object was almost tangible. ‘‘This book, containing all these ideas that were so important to me. They were picking it up and leaving with it, and it was such a wonderful literalization of the transmission of ideas.’’

Love Among the Ruins

At the New York Times, Edmund White examines our enduring fascination with the New York of the 1970s:

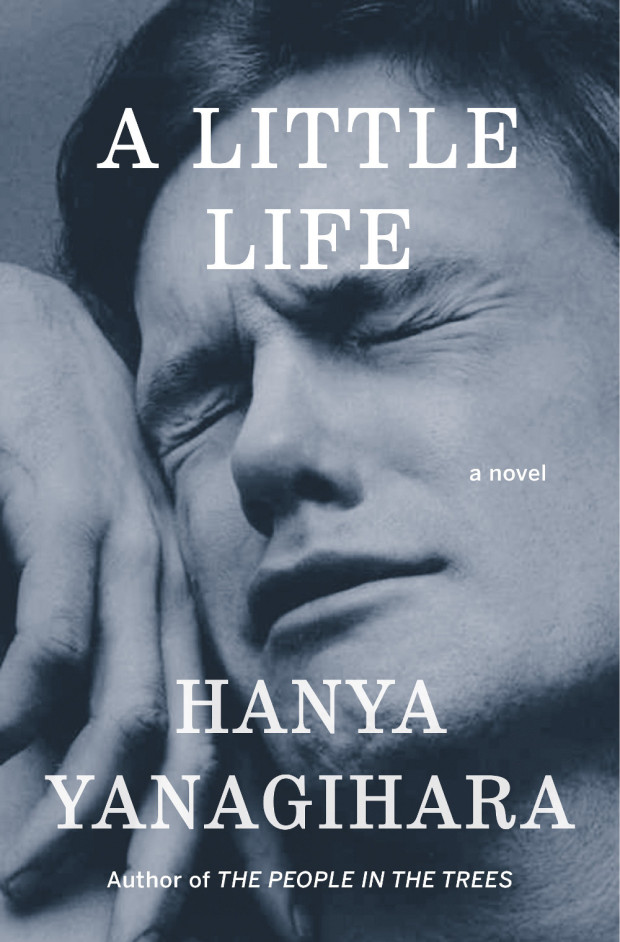

Recently there’s been, in TV and film and certainly in books, an intense yearning for a specific five-year period in New York City, those years between the blackout in 1977, and 1982, when AIDS was finally named by the Centers for Disease Control. First was Rachel Kushner’s 2013 novel ‘‘The Flamethrowers,’’ whose heroine is a sharp-eyed bystander in the SoHo art scene, and now… ‘‘City on Fire’’ by Garth Risk Hallberg, which also concerns itself with the same time period. There are two television series in development that take place in the late 1970s as well, one directed by Martin Scorsese and co-written with Mick Jagger; the other by Baz Luhrmann. Next year, the Whitney will mount the first retrospective of David Wojnarowicz, the ultimate East Village grunge artist, in over 15 years; the work of his lover, the photographer Peter Hujar — which has recently been used both for an advertising campaign for the men’s wear designer Patrik Ervell and on the cover of… Hanya Yanagihara’s novel ‘‘A Little Life’’ — will be the subject of a forthcoming retrospective at New York’s Morgan Library.

COLLECTIVELY, THESE WORKS express a craving for the city that, while at its worst, was also more democratic: a place and a time in which, rich or poor, you were stuck together in the misery (and the freedom) of the place, where not even money could insulate you. They are a reaction to what feels like a safer, more burnished and efficient (but cornerless and predictable) city. Even those of us who claim not to miss those years don’t quite sound convinced. ‘‘Well, I sure don’t have nostalgia about being mugged,’’ John Waters told me. Though then he continued: ‘‘But I do get a little weary when I realize that if anybody could find one dangerous block left in the city, there’d be a stampede of restaurant owners fighting each other off to open there first. It seems almost impossible to remember that just going out in New York was once dangerous. Do any artistic troublemakers want to feel that their city may be the safest in America? Who’s going to write a book about walking the safe streets of Manhattan? It’s always right before a storm that the air is filled with dangerous possibilities.’’

Similiarly, at the Guardian, Glenn Kenny looks at our obsession with the New York of Lou Reed and Patti Smith:

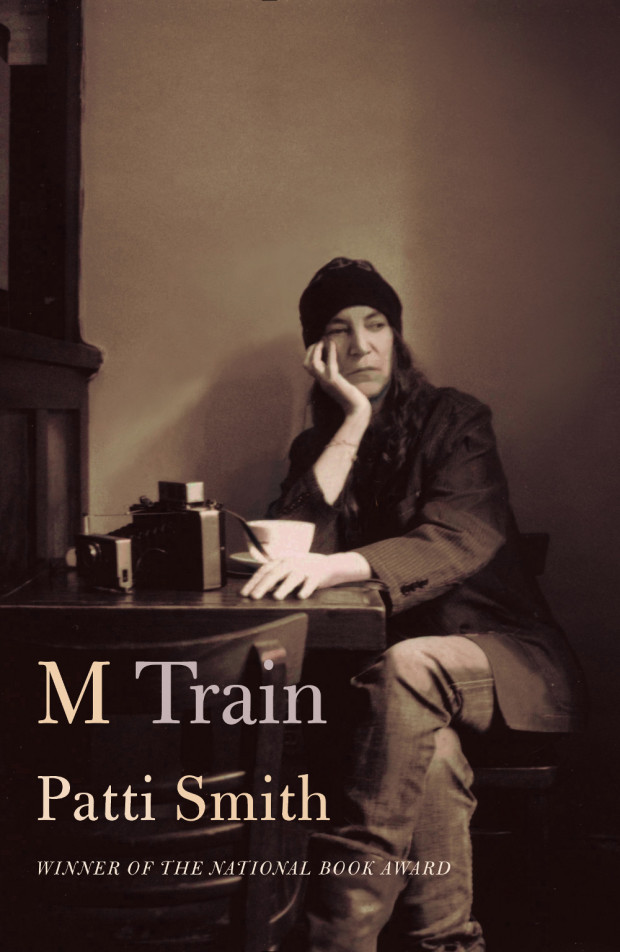

Comments closedThe New York we aspired to was Lou [Reed]’s, not Liza Minnelli’s, or a little later, Frank Sinatra’s. (The New York we aspired to was also Martin Scorsese’s, too, as it happened, and it’s almost entirely forgotten that it’s in his movie of the same name that the future anthem New York, New York made its first bow.) And these days, “wild side” New York is gazed at in rearview with fervent affection, in works by Edmund White, Patti Smith, Brad Gooch and others. (Not to mention those, like Garth Risk Hallberg or Rachel Kushner, who are too young to have their own memories to work with.) Smith’s books, in particular, seem to have hit a nerve. Her new book M Train is a more impressionistic sequel to her National Book award winning memoir of 2011, Just Kids, which is currently being developed as – weirdly enough, for me and perhaps for her – a Showtime TV miniseries.

The place these books conjure is both very scary, and very exhilarating. Not a place where some kind of arty misfit or wannabe arty necessarily wanted to live, but rather a place where one such creature could live. And hence, a place where one such young creature had to live.

A Secret History of Manhattan’s Book Trade

Don’t miss Dwight Garner’s New York Times review of Martial Bliss.: The Story of the Military Bookman, Margaretta Barton Colt’s account of running an antiquarian bookstore in Manhattan that sold only military titles. If you ever worked in an independent bookstore, you’ll probably relate…

Comments closedHistorians and journalists were devoted to the store, and leaned on it for their research. No one is lonelier than the author of a forgotten book. Ms. Colt speaks for many writers who walked into the Military Bookman when she says of one, “He loved to come to a place where the denizens knew what he had done”…

…Ms. Colt, who had previously worked in publishing, didn’t suffer fools — or ghouls. Here she is on one customer: “Lean and mean, with a crew cut, he was a real right-winger, collecting Holocaust memorabilia while being a Holocaust denier: a misanthrope with a sour sense of humor and guns in a secret closet.”

The store kept sometimes mischievous notes on its customers. These had observations like “tire-kicker, quote-dropper, reservation-dropper (particularly heinous), unredeemed check-bouncer (even worse). Also: cheapskate, picky, SS tendencies, questionable dealings, edition or d/j freak, and other sins and misdemeanors.” (The “d/j” refers to dust jackets.)

If it sounds as if the patrons were a band of brothers, yes, they were mostly men. The store maintained a comfortable chair for wives and girlfriends. Ms. Colt, who loved her work, writes terrifically about trying to maintain her sang-froid in this testicular environment.

Robert Frank: The Man Who Saw America

This weekend’s New York Times Magazine has a remarkable profile of photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank by writer Nicholas Dawidoff:

Frank absorbed artistic influences all over New York. Edward Hopper’s moody office-scapes, restaurant interiors and gas pumps were not in fashion when Frank discovered the painter: ‘‘So clear and so decisive. The human form in it. You look twice — what’s this guy waiting for? What’s he looking at? The simplicity of two facing each other. A man in a chair.’’ Frank’s creative day to day was informed by the Abstract Expressionist painters he lived among. Through his window, Frank studied Willem de Kooning pacing his studio in his underwear, pausing at his easel and then walking the floor some more. ‘‘I was a very silent unobserved watcher of this man at work. It meant a lot to me. It encouraged me to pace up and down and struggle.’’ He also saw the downside of an artist’s life: ‘‘I used to watch de Kooning work, and then I’d walk down the street and see him drinking and lying in the gutter. Somebody’s bringing him upstairs. You drink because you have doubts. Things seem to crumble around you.’’

Online, the Times also revisits The Americans, Frank’s best known work and “one of the most influential photography books of all time.”

The Endless Combinations of Robert Rauschenberg

At the New York Times, Dan Chiasson visits the archive of the late Robert Rauschenberg, currently housed in a high-security warehouse in Westchester, N.Y.. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, it looks “a little like a cross between Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu and a suburban Lowe’s”:

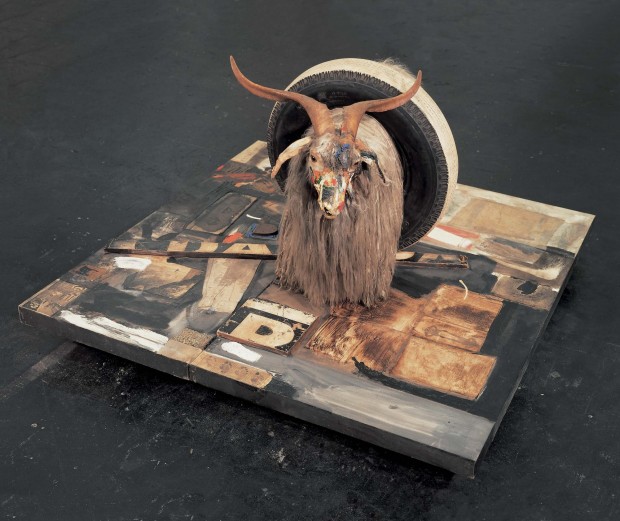

Comments closedA source material, for Rauschenberg, could have been almost anything. Among the most prolific and consistently surprising American artists, he worked for over 50 years in a variety of media from feathers, stuffed goats, socks and neckties to cardboard, grass and scrap metal, in genres including choreography, costume design, photography, printmaking and painting. He is most famous for the “combine,” a form he more or less invented that merged three-dimensional collages with sculpture, sometimes with the batty ingenuity of a Rube Goldberg. Few works capture so arrestingly the process that brought them into being: In a finished Rauschenberg, you see a goat, a tire, a tennis ball, but more than that, you see the insights that brought them together. Each component keeps its integrity within a composition in which everything contributes to a profound effect of overall beauty. Indeed, few artists of his era so unabashedly strove for beauty, even majesty: The logic of his work, beginning with cast-offs and flotsam, demanded it. It was the dare he put to himself in everything he made.