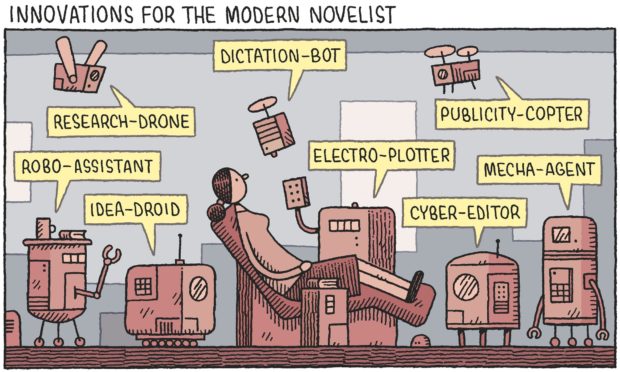

Tom Gauld for The Guardian. Who needs people?

1 CommentCategory: Authors

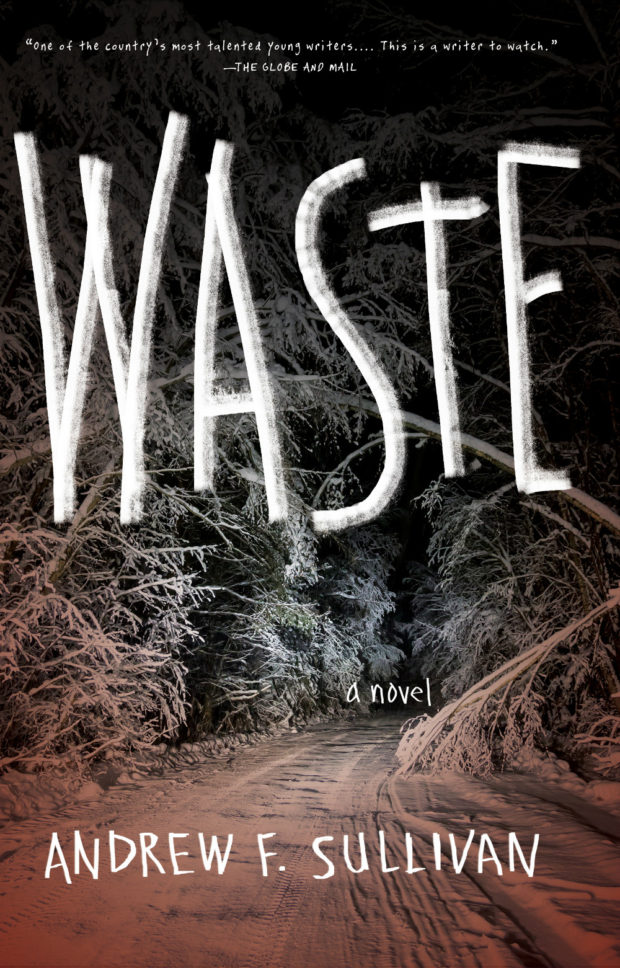

Find Your Stories in the Dirt

I mentioned Andrew F. Sullivan’s piece on High-Rise last week, and I recently spoke to the author about his own novel WASTE, and about influence of David Lynch on his writing in a Q & A for Publishers Group Canada:

Initially, I think I was very resistant to Lynch. I think I thought a lot of it was just nonsense for the sake of nonsense. It was Blue Velvet that won me over, that showed me you could implicate and confront your audience, you could tell a sad, vicious truth and people would want to hear it/see it. Lynch opened up so many opportunities to leave the explanation out, to make the work immersive and unsettling while still dancing around the established conventions for storytelling. What he was doing seemed very singular, but also invested in the everyday, in waking up, going to work, putting in the hours. He created a world, especially in Twin Peaks, that began as just slightly askew, plausible even. He lured you into the nightmare and then told you it was real. And everyone questions the theories their friends have, there is no code to break. His work exposes the peculiarities of each audience member in their own response—their passions, fears and obsessions. How can they make this story make sense? What demons does it awaken?

Lynch is still doing that. He is always doing that.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Title Fight

At The Paris Review blog, author Tony Tulathimutte (PRIVATE CITIZENS) considers how the titles of books get chosen:

Every literary generation has its naming conventions, and it’s as hard to imagine the sixty-five-word original title for Robinson Crusoe passing muster today as it is to imagine a nineteenth-century novel called Never Let Me Go. It’s easy to spot the fashions of our publishing moment: short-story collections are named after the collection’s centerpiece practically by default. Titles for longer literary works are often staked to a central relationship—The Time Traveler’s Wife, The Abortionist’s Daughter, The Orphan Master’s Son—or a group in a setting: The Swans of Fifth Avenue, The Mystics of Mile End, The Dogs of Littlefield. Publishing favors the memorable, the concrete, and the vivid; it also has grammatical preferences, like solitary adjectives (Mislaid, Thrown, Wild, Lit), rousing imperatives (See Me, Find Me, Find Her, Lean In), and quirky pleonasms like Everything Here Is the Best Thing Ever or What’s Important Is Feeling… And for whatever reason—maybe a surge of interest in young women’s lives, maybe Lena Dunham—we may soon hit Peak Girl, with The Girl on the Train, A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, Girl Through Glass, Girls on Fire, Girl at War, Gone Girl, The Girls …

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

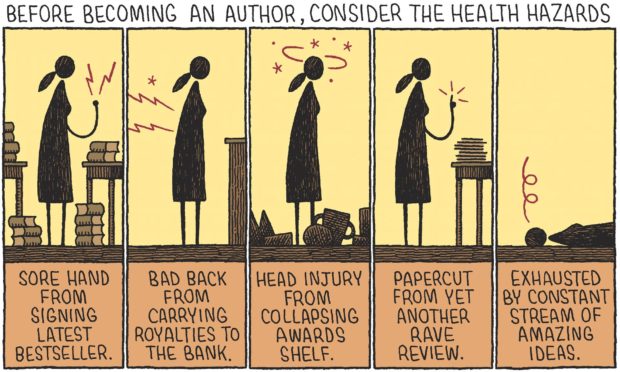

Author Health Hazards

Tom Gauld for The Guardian.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Robert Caro on New York

At The Gothamist, Christopher Robbins talks to writer Robert Caro about New York and The Power Broker, his classic Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of city planner Robert Moses:

Moses had done something no one else had ever done. Everyone thought power comes from being elected. He wasn’t elected, he realizes he’s never going to get elected to anything, so he’s got to figure out a way to get all this power without getting elected, and he does it. I didn’t understand it, no one else understood it, even La Guardia says to him, “Don’t tell me what to do,” or whatever the quote is, “I’m the boss, you just work for me.”

And Moses writes, and I saw this letter in La Guardia’s papers, he sends back the letter and he writes across it, “You’d better read the contracts, mayor.”

I gradually came to understand that because he had done this thing, that no one else had ever done, gotten all this power without being elected, if I could find out how he did it and explain how he did it, I would be explaining something that no one else understood and I thought they really should understand, which is, how does power really work in cities? Not what we’re taught in textbooks, but what’s the raw, bottom, naked essence of real power?

I’m writing this book, and I suddenly say, God, this isn’t really a biography, this is a book about political power.

My favourite part of the interview, however, is at the beginning when Caro asks questions about The Gothamist. His response to Robbins’ explanation of Chartbeat is priceless:

What you just said is the worst thing I ever heard.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

George Saunders: On Story

Storytelling, at least from my experience of it… I think it’s a stand-in for day to day life. So, when you come to a story with this attitude we’ve been talking about, which is kind of hopeful, generous, not to pushy. It’s like ‘well, what are you? I don’t know.’ You know, when you try to leave your ideas about the story at the door… those things are so much like what you do with the person in your life that you love. You come back to them again and again and try to intuit their real expansiveness, and you try to keep them close to you, you try to give them the benefit of the doubt. So in that sense you could see revision as a form of active love. It’s actually love in progress, I guess.

Author George Saunders on story:

These unadorned outtakes of Saunders just talking direct to camera about his writing process are even better:

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

George Saunders Writing Education

The New Yorker has a lovely essay by George Saunders, excerpted from a new book called A Manner of Being: Writers on Their Mentors, on his education as a writer:

For me, a light goes on: we are supposed to be—are required to be—interesting. We’re not only allowed to think about audience, we’d better. What we’re doing in writing is not all that different from what we’ve been doing all our lives, i.e., using our personalities as a way of coping with life. Writing is about charm, about finding and accessing and honing ones’ particular charms. To say that “a light goes on” is not quite right—it’s more like: a fixture gets installed. Only many years later… will the light go on.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

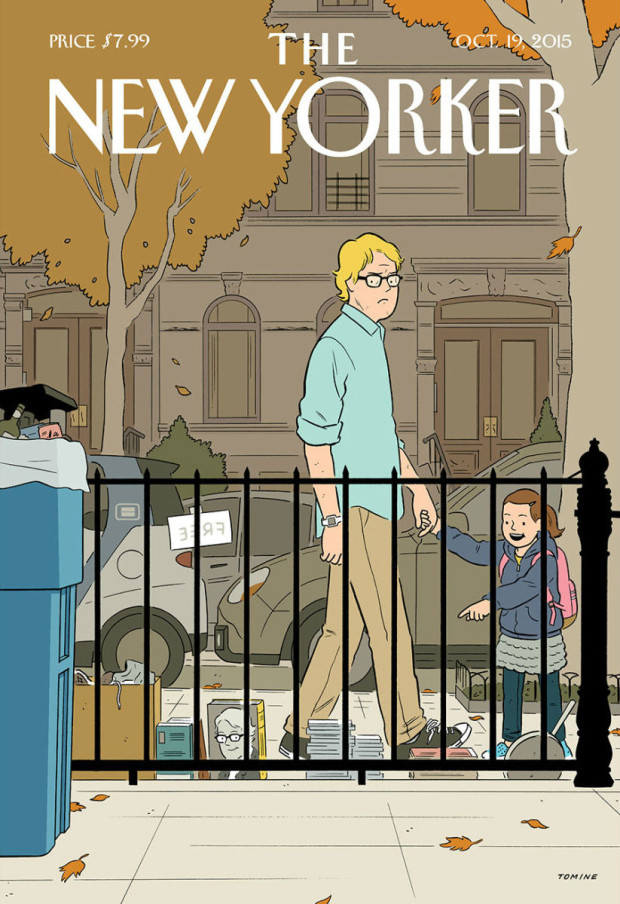

Recognition

Adrian Tomine’s latest cover for The New Yorker. Adrian’s new book, Killing and Dying, is out now.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

The Inner-Space of J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise

With the release of the Ben Wheatley movie adaptation starring Tom Hiddleston imminent, Chris Hall looks at High-Rise and the ‘inner-space’ of J. G. Ballard’s science fiction for The Guardian:

High-Rise is the final part of a quartet of novels – the first three are The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), Crash (1973) and Concrete Island (1974) – with each book seeded in the previous one. Thematically High-Rise follows on from Concrete Island with its typically Ballardian hypothesis: “Can we overcome fear, hunger, isolation, and find the courage and cunning to defeat anything that the elements can throw at us?” What links all of them is the exploration of gated communities, physical and psychological, a theme that is suggestive of Ballard’s childhood experiences interned by the Japanese in a prisoner-of-war camp on the outskirts of Shanghai in the 1940s. It was, he always claimed, an experience he enjoyed.

The built environment is not a backdrop, rather it is integral and distinctive in its recurring imagery – from abandoned runways, to curvilinear flyovers and those endlessly mysterious drained swimming pools. Perhaps more than any other writer, he focused on his characters’ physical surroundings and the effects they had on their psyches. Ballard, who died in 2009, was also interested in the latent content of buildings, what they represented psychologically. Or, as he once obliquely put it, “does the angle between two walls have a happy ending?” – by which he meant that we project narrative on to external reality, that the imagination remakes the world. In Ballard’s fiction, nothing is taken at face value.

In High-Rise and Concrete Island especially, Ballard examines the flip side to what he called the “overlit realm ruled by advertising and pseudo-events, science and pornography” that The Atrocity Exhibition and Crash mapped out. Under-imagined or liminal spaces, such as multi-storey car parks and motorway flyovers, act as metaphors for the parts of ourselves that we ignore or are unaware of. His characters are often forced to assess the physical surroundings and, by extension, themselves rather than to take them for granted.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

The Truth of Life: Paula Fox on Desperate Characters

At Longreads, Sari Botton talks to author Paula Fox talks about the latest reissue of her 1970 novel Desperate Characters:

It’s for all kinds of tension, not just racial, but class—the poor, who don’t have money or success, against the well-to-do. There are all these antagonisms… We live by pressing our palms against the skulls of the people whom we climb over. The sense of that is very strong in human society. Sometimes it’s based on possessions, or looks, or color, or experience, or history, and all these various things that we make judgments out of.

If you haven’t read Desperate Characters — and it’s a pretty perfect read if you’re stuck in the city this summer — Longreads also has an excerpt.

The cover of the W. W. Norton’s new edition (pictured above) was designed by Yang Kim.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

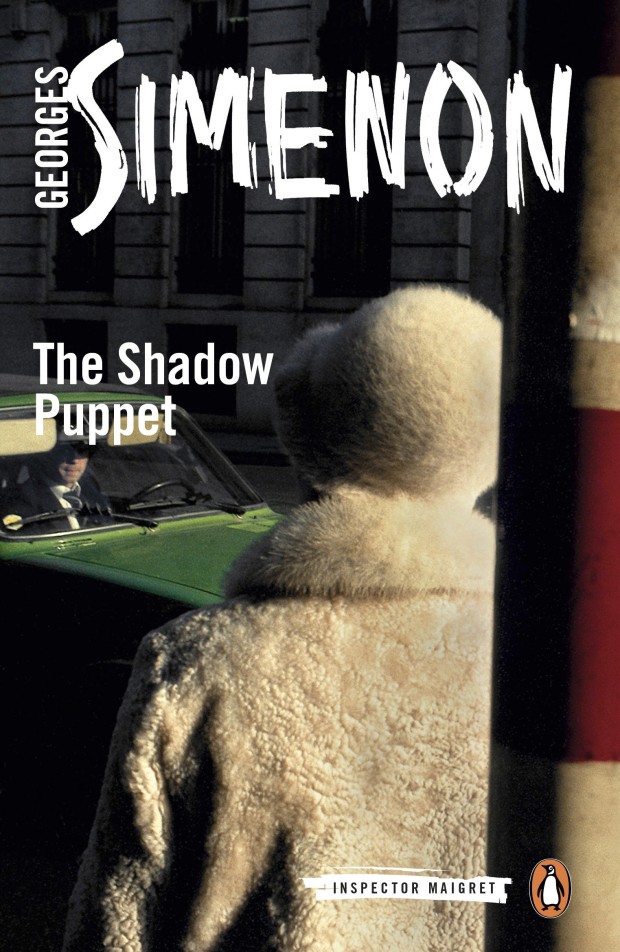

Simenon’s Island of Bad Dreams

At the NYRB Blog, John Banville reviews Georges Simenon’s novel The Mahé Circle, translated into English for the first time and now available from Penguin Classics:

Simenon was a driven creature, who in his lifetime wrote more than four hundred books, drank and womanized incessantly, and, in his younger days, roamed the world in frantic search of he knew not what. His mother despised him; his long-suffering wife wrote a roman à clef in which she portrayed him as a rampaging egotist—“His voice rang through the house from morning to night, and when he was out it was as though the silence was awaiting his return.” Most calamitous of all, his daughter Marie-Jo, who adored and idolized him—as a child she asked him one day to buy her a gold wedding ring—killed herself at the age of twenty-five. He was, all his life, a spirit in flight from others and from himself, and he is present, often lightly disguised, in every one of his books.

Penguin are reissuing Simenon at an astonishing clip. Along side his ‘romans durs’ like The Mahé Circle, they are publishing new translations of all 75 Maigret novels with covers featuring specially commissioned photographs by Magnum photographer Harry Gruyaert:

Earlier this year, Scott Bradfield also wrote about the Belgian author for the New York Times:

In many ways, the Maigrets were a sort of comfort food — the books that Simenon wrote to recover from the physical and psychological stress of writing his better, and far less comforting, novels. In these non-Maigret “thrillers,” often referred to as the romans durs (but to most aficionados known simply as the “Simenons”), the central, usually male character is lured from the stultifying cocoon of himself — and his suburban, oppressively Francophile (and often mother-dominated) life — into a wider, vertiginous world of sexual and philosophical peril, where violence, whether it occurs or only threatens to occur, feels like too much freedom coming at a guy far more quickly than he can handle.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Tim Parks on Where I’m Reading From

At BOMB Magazine, writer Tim Park discusses his new book Where I’m Reading From, a collection of his essays from the NYRB Blog, with Scott Esposito (co-author of The End of Oulipo):

In a way, this book is an autobiography of someone brought up with a very particular relation to books, in a religious family, in an English literary tradition, who on becoming an adult, for private personal reasons, set himself literary goals that were gradually revealed as spurious. Also, it’s about a person from the literary center—English, London— who has spent more than thirty years in another country, Italy, that is out of the literary mainstream. And a writer who also, by chance, became a translator and went on to teach translation. My life has been a long process of awakening to the reality, the changing reality, of the contemporary book world, which is a million miles from the naïve vision I had when I started writing books at twenty-two. Since it is in the publishers’ interests, and indeed the University’s, to sustain a false picture of what the book world is like and what the contemporary experience of books amounts to, my articles were a response to this, and an attempt to get my own head straight about what I’m really doing and the environment I move in. One is seeking at last to be unblinkered about it all.

And, if you missed it, Park reviewed What We See When Read by designer Peter Mendelsund on the NYRB Blog earlier this month:

One of the pleasures of his book is his honesty and perplexity at the discovery that every account he offers of the process of visualization very quickly falls apart under pressure. We do not really “see” characters such as Anna Karenina or Captain Ahab, he concludes, or indeed the places described in novels, and insofar as we do perhaps see or glimpse them, what we are seeing is something we have imagined, not what the author saw. Even when there are illustrations, as in many nineteenth-century novels, they only impose their view of the characters very briefly. A couple of pages later they have become as fluid and vague as so much of visual memory. At one point Mendelsund posits the idea that perhaps we read in order not to be oppressed by the visual, in order not to see.

(Pictured above is the cover of the UK edition, published by Harvill Secker in December last year, of Where I’m Reading From designed by James Paul Jones. The US edition, which has a more utilitarian cover, was just published by New York Review of Books)

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)