I first came across the London-based (and wonderfully-named) design studio We Made This by way of founder Alistair Hall’s prodigious collections of ephemera and found type on Flickr. The chances are I found these either via Ace Jet 170, a fellow designer and collector (and cyclist) who I interviewed last week, or Alistair’s page on Ffffound. It wasn’t until later than I discovered that We Made This also designed book covers and had actually worked with David Pearson on several covers for Penguin’s Great Ideas series.

More recently, We Made This has come to the attention of the literary community for the stylish and witty designs for the Ministry of Stories, and its fantastical shop front Hoxton Street Monster Supplies. The bold, flat typographic designs for the Hoxton Street Monster Supplies store are, of course, characteristic of the work produced by We Made This — taking inspiration from the best of British post-war design and Alistair’s love of printed vintage ephemera to produce something sharp, modern and irreverent but also, somehow, local and warm.

Alistair and I chatted by email.

When did you first become interested in design?

I did art at A-level, and loved it, and the artists I gravitated towards tended to have a fairly graphic sensibility – Jasper Johns, Richard Long, Jenny Holzer, David Hockney. Anything with a bit of typography caught my eye. But I didn’t realise that graphic design existed as a separate discipline, and certainly not as a career. It was never really talked about. So I studied Art History and English at Leeds University, then worked as a production assistant on TV commercials for a year or so. While I was working out what to do next, I was vaguely thinking about moving into films, so I read the BFI book Inside Stories: Diaries of British Film-makers at Work. In the book, the producer Julie Baines talks about going to see the proofs of the poster for her film. It was like a lightbulb went on in my head – “Ah, that’s what I want to do. Make posters.” So in 1999 I went to Central Saint Martins to do the BA Graphics course, and adored it – particularly when it came to the physical making of stuff – screenprinting, letterpress, etching, bookbinding, and photography (this was before digital cameras had really got going).

Is the joy of actually making things yourself integral to what you do?

Hell yes. It’s like therapy. In fact, it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. Running a blog, as I’m sure you know, is hugely satisfying – it generates fascinating conversations with people from across the design spectrum, and from across the planet. But crikey it eats up a lot of time! And having run the We Made This blog for coming up on six years, I think this year I’m going focus on it less, and use some of the time I was spending on the blog to make some actual physical stuff.

Why did you decide to start your own agency? What were you doing before?

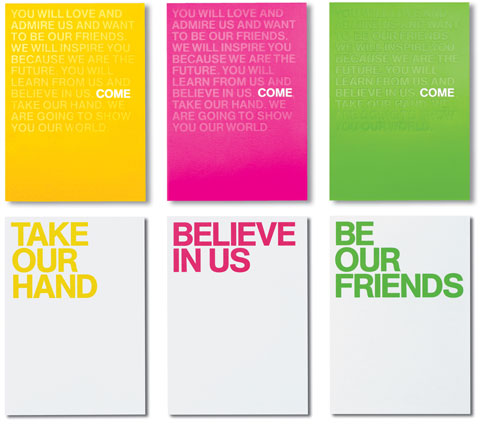

When I left college I was lucky enough to get a place at the design studio CDT, which was then being run by the lovely Mike Dempsey (the D of CDT). The studio did a fine mix of branding, print, editorial and environmental work – I spent a year and a half there, and learnt a vast amount. My favourite job there was the work we did for the Royal College of Art’s Summer Shows in 2003, for which I wrote and set a chunk of copy that we used on invitations, leaflets, signage and the catalogue. It was fairly tongue in cheek, but a lot of the students hated it. At around that time NESTA launched a short residential course that helped young creatives to set up businesses, and I got a place on that (as did a few of the students who’d been at the Royal College – there was a distincly uncomfortable silence once I owned up to that bit of work). The course was brilliant, and as soon as it finished, I handed in my resignation and set up We Made This.

What interests you about ephemera?

Well, I guess there’s a few things. There’s that feeling that you’re discovering something that no-one else necessarily knows about – these things aren’t design classics by big name designers, they’re little bits and bobs created by anonymous designers. I suppose I must feel some affinity with that… They’re enormously evocative of different periods, so there’s something there about the joy of wallowing in the past – that can be as much about the language used on them as on the design itself. Then there’s the fact that a lot of it is quite utilitarian, almost un-designed, with function dictating form, which always has an inherent beauty and honesty. Mainly though, I think all designers are just visual magpies – it’s in our DNA to get woefully overexcited about old bits of paper and old signs, and to want to take them home to feather our nests.

Do you collect specific kinds of things?

No, I’m way too undisciplined for that. I guess I do loosely focus on design from around the 1890s through to the 1950s. I tend to find most of my stuff at the regular Ephemera Society fairs in London – they’re brilliant sales that happen every few months, where ephemera traders get together and sell their wares: old luggage labels, theatre playbills, invoices, maps, all that kind of thing.

Where else do you look for inspiration?

Well, I think the most important part of the design process is research, and you never really know where that might lead you. If I was being unecessarily fanciful, I’d say it’s a bit like being a private detective – the brief is the case, and the solution to the case is out there somewhere. You just have to know where to look, who to interrogate. But you don’t have to wear a trenchcoat.

I might start with some online research but I try to move to something physical as quickly as possible. Living in London we’re blessed with a vast wealth of fantastic libraries, museums and galleries, and I often find myself heading to them to find specific visual references. The City of London Libraries’ online catalogue is often one of my first points of call – of the libraries it covers, the St Bride Library is particularly lovely, though at the time of writing, it’s open by appointment only.

I have a Ffffound page too, which is useful as an online scrapbook for keeping track of any visual bits online that catch my eye. Though we were discussing in the studio the other day whether one of the dangers of the web is that we’re all looking at the same stuff at the same time. A particular style can become omnipresent very quickly – it’s called the world wide web for a good reason – and it’s possible that regional design styles are rather fading away as a result, and everything is becoming a tad homogeneous. The web is great, but you know, approach with caution.

What was it like working with David Pearson on the Great Ideas series?

Hideous. A really unpleasant experience. Although he comes across as one of the loveliest people you could hope to meet, what a lot of people don’t realise about Dave is that he has borderline psychopathic tendencies that often manifest themselves in verbal, and occasionally physical, abuse.

Actually, it was annoyingly pleasurable. I think he was very skilled at knowing which covers each of us (the series was designed by David himself, Phil Baines, Catherine Dixon and me) would work well on. He pretty much let us get on with it, providing just a few gentle nudges here and there. He has a very thoughtful approach to design – in fact, I think he’d make an incredible art director. (If he can get a grip on the psychopathy, obviously.) Of course, the brief was just a gift. And after the books started selling by the bucketload, I think Penguin were happy to let most of the cover designs sail through.

Do you often get asked to design book covers?

Not as often as I’d like. Designing books is generally a real pleasure, particularly as you have such a concrete thing at the end of it. (Well, you have done historically… more on that below.) But I’m very lucky that I get to work on such a breadth of different types of work – though I do sometimes worry that I’m a jack of all trades, master of none. Maybe I should start focusing a bit more…

How did you get involved in the Ministry of Stories?

That all came about after I saw the film of Dave Eggers’ inspiring TED talk about his brilliant 826 literacy project. I posted the film on our blog, and asked if anyone was going to be setting up something similar in London. On the back of that post, a few of us got together and chatted loosely about how a London version of 826 might work. Things pootled along gently for a while, until Lucy Macnab and Ben Payne (the brilliant project directors) secured some funding, at the same time as Nick Hornby, who had been thinking about setting up something similar himself, joined the gang.

The Ministry follows the model of the 826 centres: a writing centre where kids aged 8-18 can get one-to-one tuition with professional writers and other volunteers; with the centres being housed behind fantastical shop fronts designed to fire the kids’ imaginations (and generate income for the writing centres). In our case, the shop is Hoxton Street Monster Supplies – Purveyor of Quality Goods for Monsters of Every Kind.

The identity for the Ministry itself grew out of an extensive series of branding workshops where hundreds of names for the project were mulled over. Lots of Post-It notes later, we eventually gravitated towards a group of names that had a slightly tongue-in-cheek air of authority about them. While that was going on, I happened to stumble upon my grandmother’s old post-war ration book, featuring the Ministry of Food logo, which seemed like the right sort of name and look for the project. There was also a fantastic exhibition about the Ministry of Food on at the Imperial War Museum, which was great for visual research.

What was the design process like for the Hoxton Street Monster Supplies project?

What was the design process like for the Hoxton Street Monster Supplies project?

Well, it was just a real pleasure really. A stupid amount of work, far more than I’d anticipated, but a real pleasure.

The story is that the shop was established in 1818, and ever since then has served the daily needs of London’s extensive monster community. It stocks a whole range of essential products for monsters. You can pick from a whole range of Tinned Fears (each of which comes with a short story from authors including Nick Hornby and Zadie Smith), a selection of Human Preserves, bars of impacted earwax, jars of daylight for vampires with S.A.D.; and a variety of other really rather fine goods.

I was given a fairly free rein by Lucy and Ben, which made things much easier, and right from the start I had a really clear idea of how it was all going to look. Of course, we had the brilliant work of the various 826 stores to use as inspiration, particularly the gorgeous Brooklyn Superhero Supply Co., designed by Sam Potts.

It was quite a full-on process though. For example, for the products: it meant coming up with the initial ideas for what they might be, working out how to produce them, naming them, writing the copy for the packaging, designing the packaging, and then actually putting the products together in the days before we opened. Fortunately we had a fantastic team of incredibly talented volunteers working on that whole process.

Have you read any interesting books lately?

I’ve just finished George Orwell’s 1984, which rather ridiculously I’d not read before, and which I loved. I’ve been going through a stage of reading some classic literature, so I’ve also recently read Dracula, Treasure Island and Huckleberry Finn. From a more contemporary point of view, I’ve also just read Alan Hollinghurst’s The Stranger’s Child, which was great – not quite up there with some of his other stuff, but still great. I definitely lean toward fiction when it comes to reading.

Do you have a favourite book?

The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, which is a kid’s book written by Neil Gaiman, and illustrated by Dave McKean, (who also did the brilliant Batman graphic novel, Arkham Asylum). It’s hilarious and beautiful.

As far as Really Serious Grown Up Fiction goes, The Master and Margarita blew me away when I read it. In fact, I think it might be about time to read it again.

On the more populist side, I love Iain M Banks’ science fiction novels, particularly the Culture novels, such as Consider Phlebas.

What does the future hold for books and print design?

Hmm. Just let me get this crystal ball powered up…

Ah, heck, I’m no expert. I’m not sure what’s going to happen next, but as someone who designs covers now and again, I have been having a think about what’s going on right now with books and print. (And it is perhaps useful here to make the distinction between literature, which is the content, and books, which are the containers of that content.) I think for literature, it’s an amazing time, with a whole raft of new ways for readers to experience the written (or typed) word. For books, obviously things are looking a bit more rocky. But I don’t think it’s all gloom and doom.

(I should point out up front that I don’t own a Kindle, nor an iPad, so I’m still effectively a luddite. I don’t have anything against either of those devices really. I already own a Mac, a Macbook Pro, and an iPhone, so I just couldn’t bring myself to rush out and grab another bit of Apple’s admittedly lovely kit.)

I think the two fundamental recent changes are: where you get your literature from, and what form that literature takes.

To set the scene, if we look just a few years back, it used to be that where you bought literature from was bookshops; or you’d borrow it from a library, or from friends and family. It would come in either hardback or paperback form – you could get audio books too, but mainly your literature came in the form of printed ink on paper pages, bound between two covers and a spine, and with some sort of hopefully appealing cover design.

So, to look at where you now buy your literature. More than likely you might go to one of the big three: Amazon, Apple, or Google; or possibly directly to a publisher’s site. You might still go along to a bookshop, where you can browse books on tables and shelves, picking them up, feeling them, touching them, even smelling them. But that’s going to become more and more unlikely.

So, you’re going to buy your chunk of literature. You might still choose to buy it in the form of a printed book. But you’re looking increasingly likely to download it, perhaps to your e-reader, with its monochrome e-ink screen and reflowable text; or perhaps to a shiny tablet, where it might be enhanced with moving images and audio. Or perhaps you’ll download it to your smartphone, either as an e-book, or as a dedicated app.

So if that’s where we’re at, how’s it working for us right now?

If we look at the first bit, the where, then I think the big problem is that no-one has really come up with anything online that beats the experience of browsing books in a shop. Obviously Amazon has all the bells and whistles of recommendations, similar items, suggestions based on your browsing history and so on, but good lord, it’s so cluttered! Apple’s iTunes is cleaner, but is still hardly an enjoyable experience. And publishers’ websites are almost universally hideous. (Canongate are perhaps the exception there, with their canongate.tv site, which at least feels like it’s heading in the right direction.)

Online retail of literature seems to still be stuck at the stage of apologetically showing you little thumbnails of book covers, as if admitting that these rectangles of pixels are just substitutes, and that the actual physical book cover will make up for it. But hey, we might never get that actual physical book cover now! So why not show us big beautiful images for the literature we’re thinking of buying. Maybe if you thought of these images as the equivalent of film posters, then you’d start to think in a different way? This should all be done so much better.

Looking at the second bit, the form our literature takes, how’s that doing?

It seems that the days of the paperback are numbered. E-readers and tablets and smartphones have dug its grave, and they’re just standing around waiting for the coffin to arrive.

The book cover, which as well as a sales tool, used to be a visual catalyst for our memories of a piece of literature, well, that’s been sidelined on e-books. As I’ve already mentioned, when you’re buying online, you’re limited to a small thumbnail. Once downloaded, sometimes you glimpse it on your device as the story first begins, but often you don’t. That seems like a lost opportunity. Surely we can do better? I saw that John Gall recently posted a possible triptych cover for an iPad edition of a book, which is an interesting new idea (unfortunately, it got rejected).

Meanwhile, the outside of your device always stays the same – after all, the device is more a library than it is a book. So the pleasure of seeing what book someone was reading, perhaps on the beach or on the tube, that’s gone. (Of course, if you want to surreptitiously read porn in public, these are happy times for you!)

Also, now that literature has become partially disconnected from its package, it starts to exist more in your head. In some ways, that could be a good thing – more pure somehow, your experience of literature no longer so influenced by the marketing team and the cover designer. But equally, an additional texture (literally and metaphorically) has been removed.

I think e-readers are pretty good, but not yet brilliant, particularly when it comes to page transitions, which are still a grimly disruptive moment in your reading, far more disruptive than turning a physical page. And you’d be more upset if you lost one than if you lost an actual book; and as everyone likes to point out, you can’t really read them in the bath. (But how many people exactly are still taking baths? And of those, how many are reading in their baths? Have they tried reading in bed? It’s far better.)

Tablets like the iPad or the Kindle Fire are great for enhanced experiences, like Faber and Touch Press’s version of T.S. Eliot’s poem The Wasetland, but less good for reading lengthy texts. Just too damn bright. Apps like Enhanced Editions’ version of Nick Cave’s The Death of Bunny Munro are interesting too, bringing lots of extra mulitmedia stuff to the party. But apparently rather costly to develop.

(If I may digress slightly, Apple’s new iBooks Author app looks quite exciting as a cheap way for designers to self-publish work. Yes it means you’re tied to the iPad rather than any other device, but still… shiny!)

From a more philosophical point of view, as Jonathan Franzen recently pointed out, there’s something distinctly unsettling about the the fact that screen based text lacks permanence. If it’s not printed, it may well change – just as in Orwell’s Ministry of Truth in 1984, where historical documents were constantly revised to suit the Party’s needs. Of course, that’s an issue for all digital media. Similarly, you can’t really lend an e-book to a friend. And can you pass on your library of e-books to your children? What will happen to all that digital content in the future?

So, overall it feels like there’s yet some work to be done with e-books before they really live up to their potential. And obviously it means that the satisfaction of producing a concrete ‘thing’ is no longer there, which is a shame. But they’re here to stay, so it’s pointless for us as designers to stick our heads in the sand while lamenting the death of the book. Better to look to the exciting new possibilities.

And, anyway, while e-books are doing their thing, they’ve also thrown fresh light on physical books – we’ve started re-examining why we love their physical form, we’ve started to treasure them again. It’s not a new area (the Folio Society has been creating beautiful high-end editions of books for years), but it’s obviously now an expanding area. You can see this with Penguin’s hardback F.Scott Fitzgeralds, and their Clothbound Classics series, as well as the gorgeous Fine Editions from White’s Books. For book designers, that opens up lots of exciting possibilities.

Gosh, I rather rambled on there. I’m sure far wiser and more people than me will have a much clearer idea of where the industry might be going.

Thanks Alistair!