In part one of our conversation, Misha Beletsky, art director at Abbeville Press, discussed his interest in the work of German-born designer and calligrapher Ismar David, the subject his recent book The Book Jackets of Ismar David, published by RIT Press. In this second and final part of our interview, Misha and talks about his own work as a designer and an art director:

How did you become interested in design?

The father of a boyhood friend in Russia was a book designer. He had a photo lab set up in his closet, took pictures of letters, and pasted them up with rubber cement. Having access to creation of the book, that holy of the holies of the bookish world I grew up in seemed like magic. I thought it was the coolest thing in the world. One day I tagged along with this friend to take night classes at the Moscow Printing Institute. Suddenly, I felt it was no longer a world I could enjoy as a guest, but a world I could be a part of. I felt it was not only something I liked doing, but an area where I could make a real difference. When I arrived in the US, one particular image from a RISD catalog influenced my decision to choose this school over others: a photograph of a calligraphy class. The unassuming black-and-white image spoke to me more than all lavish and clever full-color catalogs of other schools not because I wanted to become a calligrapher, but because I knew this was a place that based its design education on a solid ground. The essential training in typography I received at RISD laid the ground for my summer internship with David R. Godine, Publisher in Boston. This small press started out as a letterpress printing shop in a barn and over the years has been responsible for more important books on book design and typography than any single publisher in this country. There I caught the bug of fine printing. I began appreciating printer’s ink, impression, and paper, and there I was indoctrinated about the proper use of old style figures and small caps. I learned to consider all elements of the book as a part of one system where the whole is more than a sum of its parts and each part is integrally related to each other. Empowered by my discovery of the letterpress, I went back to school to spend my Senior year hand-setting metal type, carving woodcuts, and printing my own limited-edition books. My first job after school designing book interiors for Alfred A. Knopf was the best way to apply the ideals of fine printing to real-life trade publishing. Knopf house style had changed little since the heady days of W.A. Dwiggins, George Salter, and Warren Chappell. I explored every nook in the corporate library, taking in every book designed by the best designers of the 30s, 40s, and 50s. Their lessons are still with me today.

Could you describe your book cover design process?

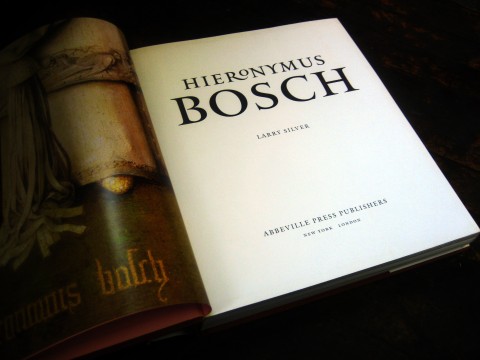

Most of the books I design are art books, which usually implies I am responsible for both the cover and the interior design. This means I have a rare privilege of making sure the cover and the interior design agree. I usually start from the inside out: I decide on the interior typography first, and then move on to the jacket. Unlike most trade books, where cover designers are only limited by their imagination and their budget in the choice of the artwork, the cover image for illustrated books usually comes from within the book. I select an image, crop it, and design the typography. This limitation made me keenly aware of how much you can do with type alone and sympathetic to the designers of the past who were able to achieve great results with limited tools.

What do you look for in a designer’s portfolio?

I look for understanding of and an eye for traditional book typography. Only a handful of portfolios out of hundreds I reviewed had it.

Do you see any prevalent trends in contemporary book design?

There is a relatively new trend of purely decorative covers and bindings by Coralie Bickford-Smith and others that seems to be a reaction to the overwhelming number of clever designs. As far as interiors go, by and large, I see a lot of unexciting work of decent quality and very little great work. I keep waiting for a resurgence of good typography, but it has not arrived yet.

What advice would you give a designer starting their career?

Read Ben Shahn’s The Shape of Content. Learn calligraphy, drawing, and printmaking. Learn letterpress printing from metal type. Manual skills cannot be emphasized enough.

Who are some of your design heroes?

Bruce Rogers, the subject of my new book. He had an almost unfathomable sensitivity to typography. In his lifetime he was famous to a point of embarrassment. Today he is hardly ever talked about. Yet, to me he remains the most versatile and the most accomplished practitioner of our craft.

Another name is Vladimir Favorsky, a towering genius of Russian graphic arts, completely forgotten outside of Russia. For many years he taught at VKhuTeMas, the Russian sister-school of the Bauhaus (which evolved into the design department of Moscow Printing Institute where I briefly studied), yet he was in opposition to the Constructivist ideas espoused by most professors there. He developed an original design philosophy of his own that integrated Avant-garde ideas with the traditional craft of wood engraving. Ironically, his fusion of the old and the new may prove more relevant today than the radical rejection of the old by his famous modernist colleagues.

What does the future hold for book cover design?

Who knows? What does the future hold for visual art or for our culture at large? It seems we’ve been living in a cultural twilight zone. We’ve tried Modernism and we came to a logical dead end, we’ve tried revolting against Modernism, and we’ve become tired of that, too. What’s next? I hope we can learn to build on top of what the previous generations learned instead of rejecting whatever the last fashion was and trying to outdo it. In the words of Goethe that Ismar David loved to quote, “What you inherited from your fathers, acquire it to make it your own.”

Thanks Misha! (And I couldn’t resist including this…)

Comments closed