I was locked a conference room last week looking at books coming out in the fall, so tI have a lot of catching up to do…

At the Financial Times, Andrew O’Hagan on the influence of other art forms on writers:

Writing novels is quiet work: it can reveal astonishments but it doesn’t usually proceed from them. Maybe that is why novelists are so often attached to second art forms that wear their physicality or their beauty outwardly. Ernest Hemingway considered bullfighting an art form and, indeed, he thought writers should be more like toreadors, brave and defiant in the face of death. For Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima it was the art of the samurai – he loved the poise, the nobility, the control, tradition, all things you would say of good prose – and he died in a ritual self-killing. But most novelists take their influence seriously without letting it take over. They are emboldened by a love of opera, as were Willa Cather and the French novelist George Sand, or by modernist painters, as Gertrude Stein was, each of these brilliant women finding in the spaciousness and drama of the other art form an enlarged sense of what they themselves were setting out to deal with on the little blank page.

And at The Guardian, O’Hagan talks to six novelists, including Kazuo Ishiguro and Sarah Hall, about their passion for a second art forms.

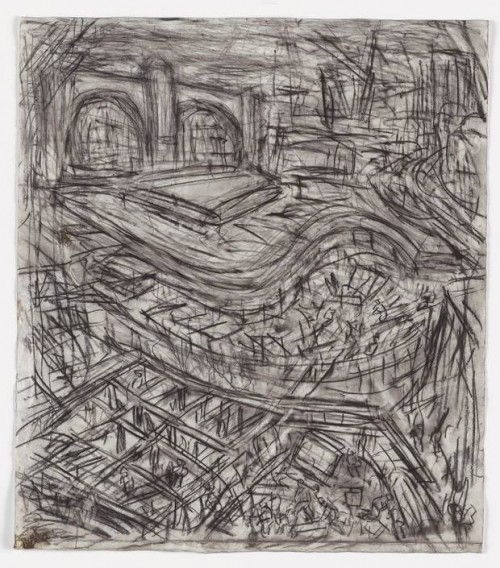

And on a somewhat related subject… Charlotte Higgins profiles painter Leon Kossoff for The Guardian:

His father, a first-generation immigrant from Ukraine, owned a bakery round the corner in Calvert Road; he was one of seven siblings. It was “absolutely not”, he says, an artistic household. “Painting didn’t exist in my family.” What drew him to art as a boy was finding himself, almost without knowing how he had got there, in the National Gallery. “At first the pictures were frightening for me – the first rooms were hung with religious paintings whose subjects were unfamiliar to me.” Later they became old friends: Kossoff spent a long period visiting the National Gallery before opening hours, working from the old masters, making not copies but what you might call translations.

An exhibition of Kossoff’s drawings and paintings of London opens at the Annely Juda Gallery May 8th.

Shuffle — At the Center for Fiction, Dawn Raffell interviews Renata Adler:

I always shuffle. And there, the computer is just a disaster because the only thing I’ve ever been compulsively neat about is typing. I type with two fingers, and so I would always make a mistake near the end of the page, and since White Out is no use, I would throw the thing out and start again at the beginning. Then along came the computer and I thought it was going to help because you can move everything around all the time and you can change every sentence 50 different ways in seconds. But that’s exactly what I don’t want, because then what was I doing? If the computer can shift everything in a split-second, then what am I doing here? That’s what I used to do so carefully. One of the things that’s almost comically a problem is AutoCorrect, and what AutoCorrect thinks I’m saying.

‘The Amanda Palmer Problem‘ — Nitsuh Abebe at Vulture:

The web offers an opportunity to fall into the open arms of fans, in ways that weren’t available before. Here’s the catch: The web also makes it near-impossible to fall into the arms of just one’s fans. Each time you dive into the crowd, some portion of the audience before you consists of observers with no interest in catching you. And you are still asking them to, because another thing the web has done is erode the ability to put something into the world that is directed only at interested parties… Telling the world all about your life can look generous to fans and like a barrage of narcissism to everyone else.

Also from New York Magazine, the faintly ridiculous ‘At Home with With Claire Messud and James Wood‘:

“There’s been a great deal of closely spaced difficulty to sort through,” she says. “You know that Katherine Mansfield story, ‘The Fly’?” It’s about a fly being slowly drowned in ink. “Well, I am the fly. Every time I hope that things will get better, somebody drops another inkblot on me. So it seems to me if there were a divine lesson it would be to stop hoping that the blots will cease, and instead to come to terms with it … At some point you have to think, All right, it’s not as if someone is promising you something easier or better. You have to be grateful to get it done at all.”

Wood talks about his recent collection of essays, The Fun Stuff, at The Spectator, and Messud’s new novel The Woman Upstairs, was published by Knopf this week.

Like this:

Like Loading...