This is my last monthly round-up for 2018. Next month I’ll post my round-up for the year. I have to confess that I have not given the blog 100% of my attention of late, so if you think that there are covers I might’ve overlooked this year please feel to send them my way for consideration.

Bitwise: A Life in Code by David Auerbach; design by Tyler Comrie (Pantheon / August 2018)

The Book of Beautiful Questions by Warren Berger; design by Tree Abraham (Bloomsbury / October 2018)

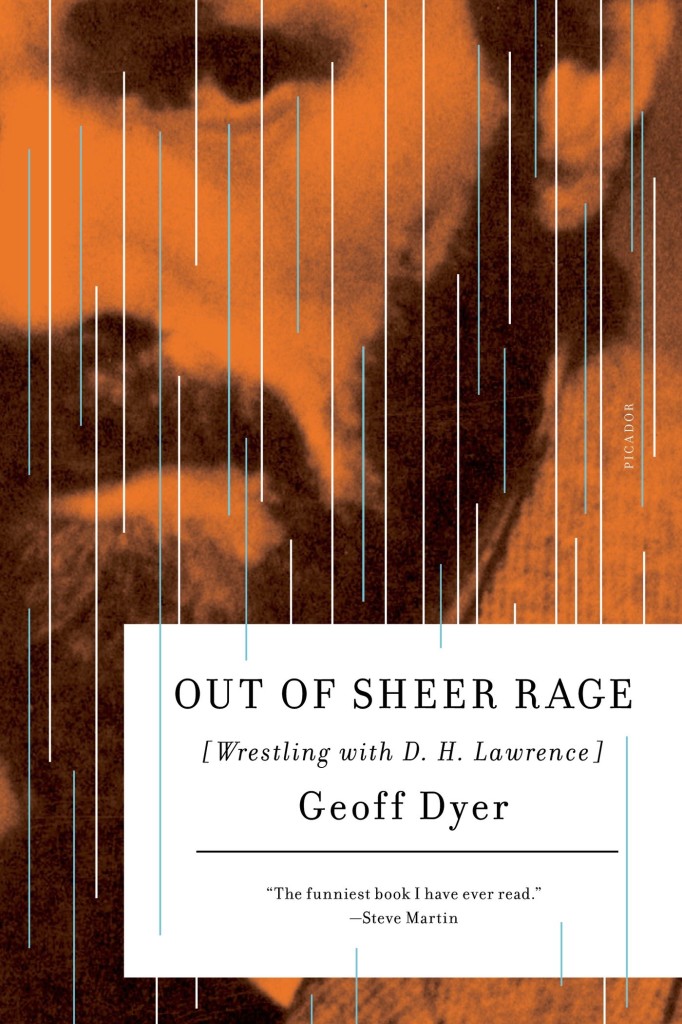

‘Broadsword Calling Danny Boy’ by Geoff Dyer; design Jim Stoddart (Penguin / October 2018)

The blackletter is similar, I believe, to the type used for the movie title / credits, and the chevrons are a nice reference to a design that appears in the movie. The Guardian reviewed the book last month if you are curious. (And someone in the UK needs to buy it for me as a Christmas present!)

The Deserters by Pamela Mulloy; design by David Drummond (Véhicule Press / September 2018)

Evening in Paradise by Lucia Berlin; design by Na Kim (Farrar, Straus and Giroux / November 2018)

Na Kim designed the cover for Welcome Home by Lucia Berlin, also released this month, too:

The cover of the UK edition of Evening in Paradise was designed by Justine Anweiler I believe. Justine designed the wonderful cover for hardback of A Manual For Cleaning Women:

Feminasty by Erin Gibson; design by Anne Twomey; photograph by Ricky Middlesworth (Grand Central / September 2018)

Usually I’m a bit reluctant to post the covers of celebrity books, but this is pretty great.

Celebrity book covers are often look beautiful — the recent memoirs by Sally Fields and Michelle Obama come to mind — but often that’s because of a glamourous photograph. The designer’s job is just to get out of the way. That makes sense from a marketing point of view, it’s just not terribly interesting from a design perspective. This feels like it has a bit more to it somehow. Or maybe it’s just more fun…

That all said, I have started to see this kind of swashy retro type pop-up more frequently of late. A couple of recent examples that come to mind are the covers of All the Beautiful Girls by Elizabeth J. Church, designed by Anna Morrison (Fourth Estate), and The Dakota Winters by Tom Barbash designed by Allison Saltzman (Ecco):

I was also reminded of Kelly Winton‘s covers designs for the reissues of Black Swans and Sex and Rage by Eve Babitz from Counterpoint.

I would guess the fonts are Bodoni or variants thereof, but no doubt someone with a better eye for type will be able to tell us for sure.

UPDATE: Anna Morrison tells me the font she used for All the Beautiful Girls is Cabernet, which just goes to show what I know. According to the ever-useful Fonts in Use, Cabernet is “an uncredited revival of Benguiat Caslon, a 1970s Photo-Lettering typeface by Ed Benguiat.” I’m pretty sure Benguiat Caslon was used for the iconic Philip Roth covers in the 1970s so I probably should’ve recognized it…

The Feral Detective by Jonathan Lethem; design Allison Saltzman; photograph Kate Bellm (Ecco Press / November 2018)

Heavy by Kiese Laymon; design by Na Kim (Scribner / October 2018)

Hippie by Paulo Coelho; design by Tyler Comrie (Knopf / September 2018)

Is this the year of the orange cover…?

The Hole by José Revueltas; design by John Gall (New Directions / November 2018)

John Gall has a new book collecting 10 years of his collages out this month too.

You can read my 2011(!) Q & A with John about his collages here.

Homeland by Walter Kempowski; design by Dan Mogford (Granta / November 2018)

Dan also designed the cover for All for Nothing by Walter Kempowski a couple of years ago:

I Do Not Trust You by Laura J.Burns & Melinda Metz; design by Olga Grlic (St. Martin’s Press / September 2018)

I had it in my mind that snaky red covers with big white type were very “in” for thrillers right now, but the only other example I could think of was the US cover for Our Kind of Cruelty by Araminta Hall designed by Alex Merto, which is really not that similar…

Perhaps I am imagining it.

The Library Book by Susan Orlean; design by Lauren Peters-Collaer (Simon & Schuster / October 2018)

Notes from the Fog by Ben Marcus; design by Jamie Keenan (Granta / September 2018)

The US cover, which I featured in a previous post, was designed by Peter Mendelsund:

Odessa Stories by Isaac Babel; design by Anna Morrison (Puhskin Press / November 2018)

Portraits Without Frames by Lev Ozerov; design by Dan Mogford (Granta / November 2018)

The Son of Black Thursday by Alejandro Jodorowsky; design by Richard Ljoenes (Restless Books / November 2018)

Richard also designed the cover of Jodorowsky’s previous novel Where the Bird Sings Best:

And take a moment to check out Richard’s online portfolio, which is new I believe.

Wasteland by W. Scott Poole; design by Jaya Miceli (Counterpoint / November 2018)

The Winters by Lisa Gabriele; design by Nayon Cho (Viking / October 2018)

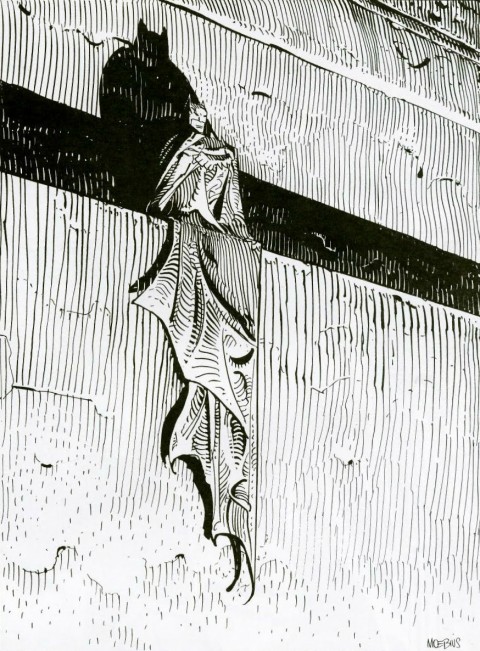

Obituary for artist Jean Giraud, AKA Moebius, in

Obituary for artist Jean Giraud, AKA Moebius, in