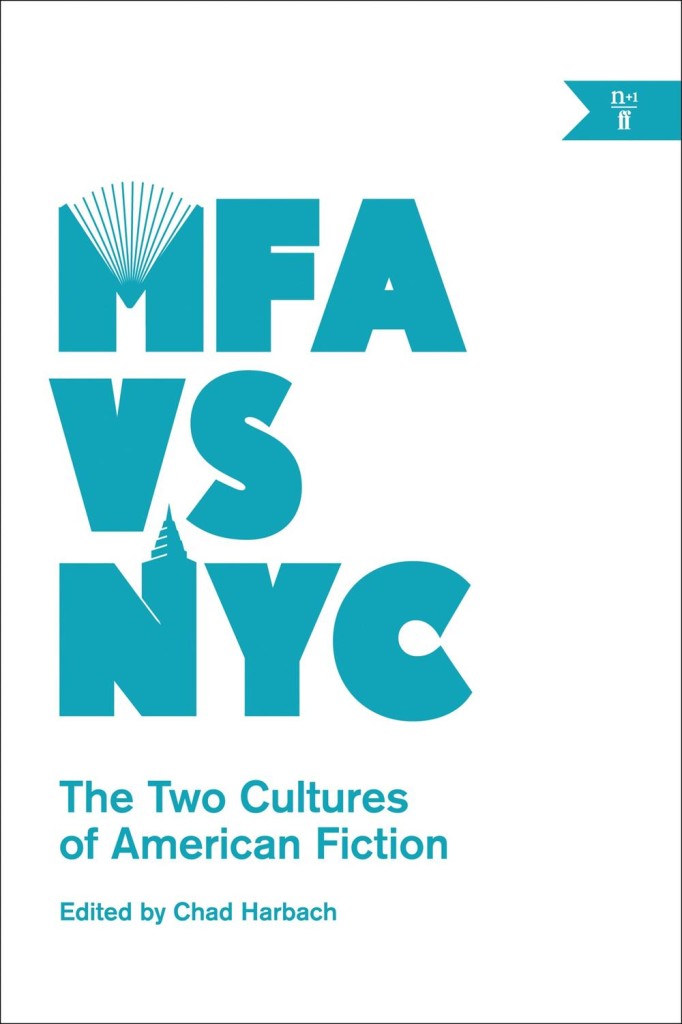

I finally just got around to reading Emily Gould‘s spiralling essay on writing and debt ‘How much my novel cost me‘ over the weekend. It’s an excerpt from the new n+1 book MFA vs NYC edited by Chad Harbach (author of The Art of Fielding), which seems like it could be essential reading for idealistic folks wishing to pursue writing as a career:

IT’S HARD TO WRITE ABOUT BEING BROKE because brokeness is so relative; “broke” people run the gamut from the trust-funded jerk whose drinks you buy because she’s “so broke right now” to the people who sleep outside the bar where she’s whining. But by summer 2012 I was broke, and in debt, and it was no one’s fault but mine. Besides a couple of freelance writing assignments, my only source of income for more than a year had come from teaching yoga, for which I got paid $40 a class. In 2011 I made $7,000.

During that $7,000 year I also routinely read from my work in front of crowds of people, spoke on panels and at colleges, and got hit up for advice by young people who were interested in emulating my career path, whose coffee I usually ended up buying after they made a halfhearted feint toward their tote bag–purses. I felt some weird obligation to them and to anyone else who might be paying attention to pretend that I wasn’t poor. Keeping up appearances, of course, only made me poorer. I’m not sure what the point of admitting all this might be, because I know that anyone who experiences a career peak in his mid-twenties will likely make the same mistakes I did, and it’s not even clear to me that they were all mistakes, unless writing a book is always a mistake, which in some sense it must be.

Interestingly, Robert McCrum touches on the financial difficulties of older authors in an article for this weekend’s The Observer

To writers of my generation, who grew up in the age of Penguin books, vinyl records and the BBC, it’s as if a cultural ecology has been wiped out. For as long as most of us can remember, every would-be writer knew the landscape of the printed word. This Georgian square was home to publishing grandees (now retired). On that high street were the booksellers (now out of business). In those twisting back streets, you could expect to find literary agents working the margins with the injured innocence of pickpockets at a synod. It was a mutually dependent ecosystem.

Publishers were toffs, booksellers trade and printers the artisan champions of liberty. Like the class system, we thought, nothing would change. The most urgent deadline was lunch. How wrong we were. The years 2007-2010 are pivotal: first… came the credit crunch. And it occurred at the very moment that the IT revolution was wrecking the livelihoods of those creative classes – film-makers, musicians and writers of all sorts – who had previously lived on their copyrights.

Gould is self-recriminating. McCrum — a former editor-in-chief at Faber and Faber — is nostalgic for a time I don’t remember (things were always better in the ‘old days’ in publishing circles). For Gould the internet is a double-edged sword — a platform and a distraction — for McCrum it has brought nothing but woe. Both seem to agree, however, that nobody is making any money, “marketing types” are awful (aren’t they though?), and being a writer is not all it’s cracked up to be…

Coincidently, Emily Gould’s new novel Friendship will be published in the US and Canada by Farrar, Straus & Giroux on July 1 (and a couple of days later in the UK by Virago). I’m not sure who designed the cover, but it is rather nice.

(NB: FSG, and n+1 / Faber & Faber are distributed in Canada by my employer Raincoast Books)

UPDATE: Leslie Jamison, author of the forthcoming essay collection The Empathy Exams (published by Graywolf Press, also distributed in Canada by Raincoast — sorry), reviews MFA vs NYC for The New Republic:

Writers throughout these essays face the shame of privilege and the specter of poverty: They join magazine mastheads to keep from going broke, or they teach to keep from going broke, or else they actually do go broke—they’re broke in Brooklyn and broke in Los Angeles. Eli Evans evokes his years living in a “warehouse on Pico and Fourth” in one perfect image, one of the most remarkable moments in the entire collection: “I once found a baby rattlesnake strangled with electrical wire and tied to a signpost.” This baby rattlesnake, apparently, is what dreams become…

Like this:

Like Loading...