A rather brilliant cover for The Yellow World by Albert Espinosa, reminiscent of a Matisse cut-out or a Paul Rand illustration, designed by Jon Gray.

The Sickly Glow — John Banville, author most recently of Ancient Light, reviews The Big Screen by David Thomson, for The Guardian:

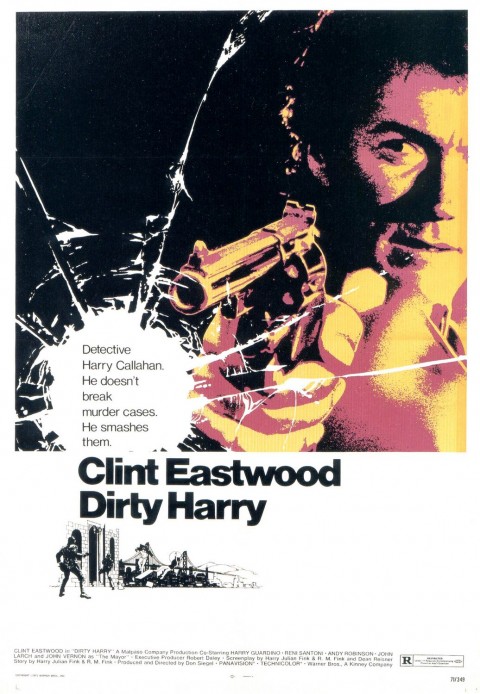

Thomson worries that something happened to the cinema around the time of Jaws, something cynical, sinister and perhaps even fatal. Part of the fun of Jaws and the other mindless thrills-and-spills imitations that it spawned, he says, “is that the commotion meant nothing. The sensation eclipsed sensibility”. This is the contentious heart of The Big Screen. The deadening process that, according to Thomson, set in the 1970s has now spread across the billions of tiny screens that infest the world, the combined sickly glow of which must be visible from outer space. Watching has become mere gaping, open-mouthed and slow-breathing. “Facebook already takes our earnest admissions about ourselves and trades them for advertising.”

You can read a short interview with Thomson about the book at The Arts Desk:

I went through a stage, particularly when I was teaching, of saying, “Well, these are the great filmmakers, let us explore them as if they were Charles Dickens or Van Gogh or someone like that.” The auteur theory. And now I’ve got to a stage where I sort of feel that every film is more like other films than anything else. Films are all alike, because the technology is more important. The director is fading away – you don’t think to ask who directs television, and yet television today in America is at a very good stage. So I’ve become increasingly interested in the technology, and what that has done to shape the format.

And on a somewhat glummer note… David Denby, movie critic at The New Yorker and author of Do the Movies Have a Future?, on the economics of Hollywood, at The New Republic:

Most of the great directors of the past—Griffith, Chaplin, Murnau, Renoir, Lang, Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Rossellini, De Sica, Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, Bergman, the young Coppola, Scorsese, and Altman, and many others—did not imagine that they were making films for a tiny audience, and they did not imagine they were making “art” movies, even though they worked with a high degree of conscious artistry. (The truculent John Ford would have glared at you with his unpatched eye if you used the word “art” in his presence.) They thought that they were making films for everyone, or at least everyone with spirit, which is a lot of people. But over the past twenty-five years, if you step back and look at the American movie scene, you see the mass-culture juggernauts, increasingly triumphs of heavy-duty digital craft, tempered by self-mockery and filling up every available corner of public space; and the tiny, morally inquiring “relationship” movies, making their modest way to a limited audience. The ironic cinema, and the earnest cinema; the mall cinema, and the art house cinema.

Viva Hate — Keith Gessen, founding editor of n+1, on Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, at The New Statesman:

They had been brought together by their mutual hatred of the universe, which for a while did a fine job of confirming their feelings about it by rejecting and ignoring them. As they began to find their way in the world it became a little harder to hate it, at least with the same intensity. And so their letters to each other dwindled: What was there to say?

They were rescued by the 1960s. Amis and Larkin managed to greet the transformations, disturbances and new thinking with shared hostility. It brought them a whole gamut of things to hate.

And finally…

Lunch with painter Frank Auerbach, at the Financial Times:

It’s funny, this business of a vocation. One starts from a motive one hardly comprehends. In the school holidays I was an office boy – I found the idea of going into an office horrifying. As a painter, I thought there would be bohemianism, freedom, and there was, but gradually the practice of art took over. As Auden says, in any crisis, the break-up of a relationship, the response is to flee to the arms of the muse. At art school you know at least as many talented students as those who became painters, but they get off the train at some point. I met Stephen Spender once, I expected a poet with a vocation but I found a civilised man, gregarious, leading a varied, entertaining, virtuous life – for whom poetry was only one of the facets. He said one of his dreams was to be a poet, the other to have a lovely life, go to France, know lots of people.

Like this:

Like Loading...