Tom Gauld celebrates Independent Bookshop Week (which was last week, but isn’t every week independent bookshop week when you think about it?)

Comments closedBooks, Design and Culture

Tom Gauld celebrates Independent Bookshop Week (which was last week, but isn’t every week independent bookshop week when you think about it?)

Comments closedAt the New York Times, Julie Bosman looks at how American bookstores have become hubs of resistance:

Comments closedPolitical organizing is perhaps a natural extension of what bookstores have done for centuries: foster discussion, provide access to history and literature, host writers and intellectuals.

“All bookstores are mission-driven to some degree — their mission is to inspire and inform, and educate if possible,” said Elaine Katzenberger, publisher and executive director of City Lights in San Francisco, a store with a long history of left-wing activism.

“When Trump was elected, everyone was just walking around saying: ‘What do I do. What do we do?’” she added. “One of the places you might find some answers is in books, in histories, in current events, even poetry.”

Welcome to The Last Bookstore is a short, inspiring documentary about Josh Spencer, owner and operator of The Last Bookstore in downtown Los Angeles:

Comments closedIn a special report, WNYC’s On the Media recently took a look at the publishing industry and print books. It covers a lot of ground — including the subversive history of adult colouring books, Amazon’s bricks-and-mortar bookstore, and South Korea’s quest for a Nobel Prize in Literature — but the opening segment, ‘Why the Publishing Industry Isn’t in Peril‘, with LA Times books editor Carolyn Kellogg is an excellent overview of the current state of US publishing:

Comments closedThe New Yorker visits the Community Bookstore in Brooklyn as owner John Scioli begins to clean out his “cavern of books” in preparation of the store’s closing in May:

Comments closed

The New York Business Journal looks why McNally Jackson is thriving, while other the city’s other independent bookstores are disappearing:

most literati agree that independent book stores are an endangered species in high-rent New York. See what’s happening right now with the St. Mark’s Bookshop, which was forced to move once and now is preparing to close for good. Or look at what’s already happened to Gotham Book Mart, Biography Bookshop, Bank Street Bookshop and even the chain store Borders Books. All are shuttered. Even Barnes & Noble has closed three large outlets in Manhattan (Astor Place, Chelsea, Lincoln Center).

But something special is brewing on Prince Street in NoLita because McNally Jackson is packed. The café is booming, the self-publishing arm is prospering, and the nightly literary events, are popular. McNally Jackson is the prime example of what it takes for an independent bookstore to succeed: operating as a triple threat of bookstore, café and publisher.

Comments closed

In a long profile for the Globe and Mail, book review editor Mark Medley visits Nicky Drumbolis owner of the singular Letters Bookshop in Thunder Bay:

Comments closedWalking through the store is an overwhelming experience. Everywhere I look I spot something I’ve never seen before and will probably never see again. I could have picked a single shelf of a single bookcase and spent my entire visit studying its contents. Not that Mr. Drumbolis would have let me do that. As we amble up and down the aisles, he is constantly narrating, constantly picking out items at random and telling their story – how he acquired it, or who published it, or whatever happened to its author – which often leads into another, entirely different story, and another book, and so on, until I can’t remember which book started the conversation in the first place.

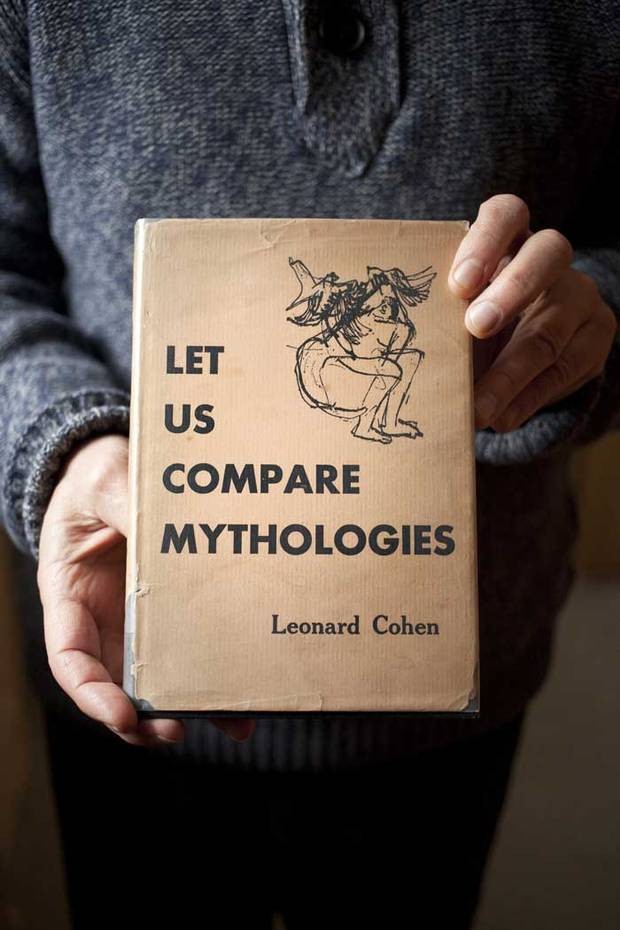

He throws around words like “shit kicker” or “heavyweight” to describe books he particularly loves, his voice growing progressively louder and more animated, the longer he talks. He pulls out a first edition of Leonard Cohen’s 1956 debut Let Us Compare Mythologies, part of what is probably the most extensive sampling in existence of Montreal’s legendary Contact Press, which helped to launch Margaret Atwood, Irving Layton, Raymond Souster and others. Now here’s his Franz Kafka collection, and over here Ezra Pound, and Charles Bukowski, and a few remaining titles from his collection of William S. Burroughs, most of which he sold years ago to David Cronenberg around the time the director was adapting the Burroughs novel, Naked Lunch.

“Henry James,” he says, tapping a shelf filled with first editions of the American master. “The guy I wanted to read cover to cover before I died. I don’t think I’ll get to it now.”

Also at The New Yorker, Brian Patrick Eha writes about the closure of Brazenhead Books, Michael Seidenberg’s secret New York bookstore:

Michael Seidenberg’s one-of-a-kind bookshop, Brazenhead Books, closed last month. For seven years, it operated out of an apartment at 235 East Eighty-fourth Street. Of course no bookstore or other business had any business being there, in that rent-stabilized apartment, so it was, strictly speaking, illegal, and because it was illegal it had to be secret. The secret was known to a small number of discreet patrons and shared strictly by word of mouth. (At first, Michael saw customers by appointment only.) Inside, the windows were blacked out and covered with shelves. On bookcases, in every room, volumes of all sizes in serried ranks rose two deep from floor to ceiling. More were stacked on desks and tables and grew in unsteady columns from the floor. There was a stereo (covered in books), a few chairs, and a large desk in the front room (likewise all but submerged), on which Michael kept a half dozen or so bottles of wine and spirits, a tower of plastic cups, and a bucket of ice.

Walking in, you might find a handful of patrons lounging on chairs with drinks in their hands, or browsing amiably, making conversation, generally about books, but often ranging widely into art, politics, personal life stories, and the history of New York. In the same way that children imagine adults living in perfect freedom, enjoying all the cookies and television they want and staying up till all hours, Michael’s shop was what a bookish child might dream up as a fantasy home for himself, a place far from any responsibilities, where he would never run out of stories.

The good news is that Seidenberg plans to reopen the store elsewhere. Until then, you can watch this video about the old location.

Comments closedDon’t miss Dwight Garner’s New York Times review of Martial Bliss.: The Story of the Military Bookman, Margaretta Barton Colt’s account of running an antiquarian bookstore in Manhattan that sold only military titles. If you ever worked in an independent bookstore, you’ll probably relate…

Comments closedHistorians and journalists were devoted to the store, and leaned on it for their research. No one is lonelier than the author of a forgotten book. Ms. Colt speaks for many writers who walked into the Military Bookman when she says of one, “He loved to come to a place where the denizens knew what he had done”…

…Ms. Colt, who had previously worked in publishing, didn’t suffer fools — or ghouls. Here she is on one customer: “Lean and mean, with a crew cut, he was a real right-winger, collecting Holocaust memorabilia while being a Holocaust denier: a misanthrope with a sour sense of humor and guns in a secret closet.”

The store kept sometimes mischievous notes on its customers. These had observations like “tire-kicker, quote-dropper, reservation-dropper (particularly heinous), unredeemed check-bouncer (even worse). Also: cheapskate, picky, SS tendencies, questionable dealings, edition or d/j freak, and other sins and misdemeanors.” (The “d/j” refers to dust jackets.)

If it sounds as if the patrons were a band of brothers, yes, they were mostly men. The store maintained a comfortable chair for wives and girlfriends. Ms. Colt, who loved her work, writes terrifically about trying to maintain her sang-froid in this testicular environment.

To mark Independent Bookshop Week in the UK, author Helen Dunmore celebrates browsing the shelves:

Comments closedReaders go their own way, and this is what frustrates governments and tantalises publishers. You can drag the reader to the water with the most brilliant advertising and marketing campaigns, but you cannot make him or her drink deep of shallow words.

No one can define the quality in a book that makes it command passionate loyalty from readers, and while some bestsellers are predictable, others have leapfrogged every idea about what readers should love. This is where physical bookshops and libraries are so important to readers, in spite of the convenience and ease of making an online purchase. We need to be able to see all the books that we don’t know about yet. Bookshops encourage browsing, dawdling and discovery. They open byways that become high roads to new fields of understanding. They don’t nag; they suggest. To be a reader in search of a book is more than to be a shopper who already knows what he or she wants to buy. Bookshops and libraries are places where books and readers come out of the private world, and make their claim on the public space. They say, visibly, how important books are to us.

Writing at the New Yorker, Adam Gopnik considers the closing of La Hune in Paris, and what is lost when a bookstore closes:

The forces that brought La Hune down are, sadly and predictably, the same forces that destroyed Rizzoli, on 57th Street, or the old Books & Co., on Madison Avenue: the ruthless depredations of the Internet (Amazon is regarded warily in France, and pays a bookstore-protection tax, but it is there), alongside the transformation upward (or is it downward?) of the inner cores of big cities into tar pits for a mono-culture of luxury. Where La Hune last stood, Dior now stands.

These laments can all be dismissed as mere nostalgia—though, since nostalgia starts the very moment our experience becomes past, it can never be so easily dismissed. And the case for minimal regret about such transformations, or easy acceptance of them, is plain enough and not hard to make. Bookstores open and they close, following the path of bright young people as migratory birds follow the sun. In Paris, good bookstores have opened in, or migrated to, the popular quartiers of the 15th and 19th arrondissements, just as a few independent bookstores in [New York] have migrated to the sunnier climes of Brooklyn. Anyway (the more impatient counter argument goes on), a bookstore is only a platform for the purchase of literature, and platforms move and change with every new age, gathering and then shedding the moss of our memories as they roll on. Someday, someone will be writing a nostalgic account of one-click shopping on Amazon. Indeed, if videocassettes had lingered longer, we’d have sad feelings about the passing of Blockbuster. Some members of Generation X probably do now.

Yet the emotions that such losses stir can’t be dismissed quite so blithely—talking to Parisian friends, I found they shared my sense of something that it would be indecent to call grief but inadequate to call sadness.

I’m actually OK with it all being nostalgia. I just like bookstores, and it makes me sad when good ones close. That said, Luc Sante’s reality-check did make me laugh:

I hate to see a bookstore close, but La Hune had to have been the most hostile bookstore in the world http://t.co/vc5i0pslOV via @adamgopnik

— Luc Sante (@luxante) June 14, 2015

Comments closed