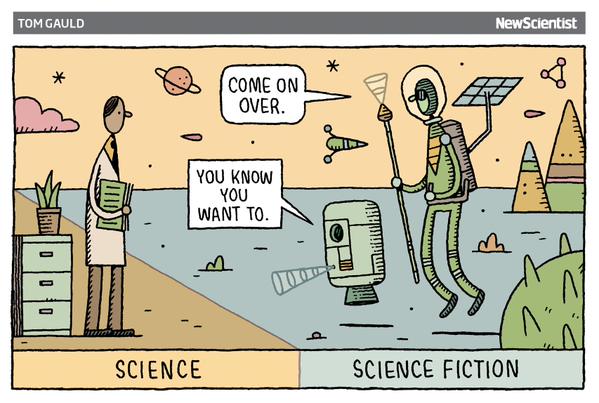

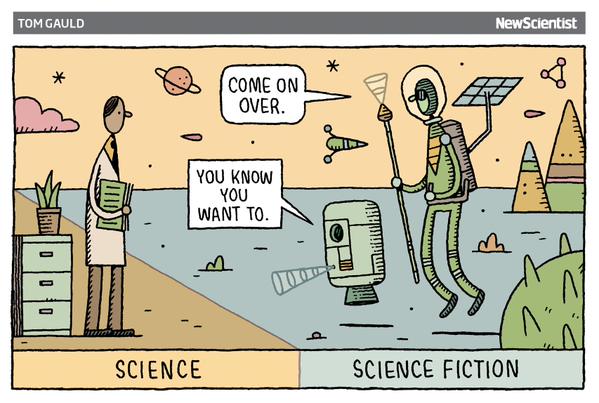

In his latest cartoon for New Scientist magazine, Tom Gauld illustrates the temptations of science fiction:

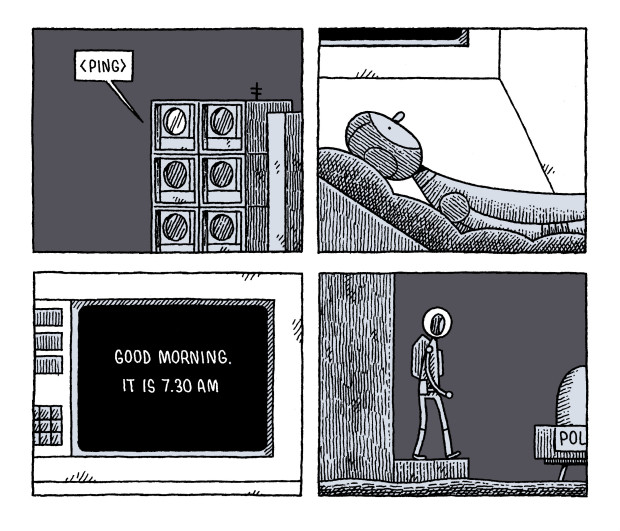

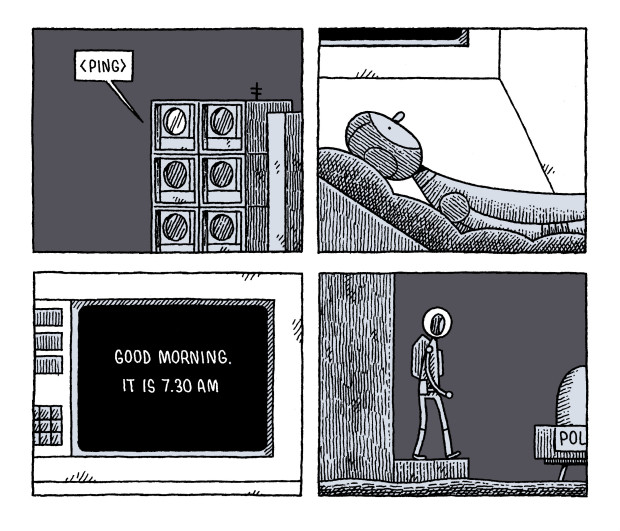

In related news, Drawn & Quarterly are going to publish Tom’s new book Mooncop next year. It looks amazing:

Books, Design and Culture

In his latest cartoon for New Scientist magazine, Tom Gauld illustrates the temptations of science fiction:

In related news, Drawn & Quarterly are going to publish Tom’s new book Mooncop next year. It looks amazing:

In what is presumably an excerpt from his new book Stuff Matters, materials scientist and engineer Mark Miodownik describes how his obsession with materials began with being attacked on the London Underground:

I was right about one thing: he didn’t have a knife. His weapon was a razor blade wrapped in tape. This tiny piece of steel, not much bigger than a postage stamp, had easily cut through five layers of my clothes, and then through the epidermis and dermis of my back in one swipe. When I saw the weapon in the police station later, I was mesmerised. As the police quizzed me, the table between us wobbled and the blade sitting on it wobbled too. In doing so it glinted in the fluorescent lights, and I saw that its steel edge was still perfect, unaffected by its afternoon’s work.

This was the birth of my obsession with materials – starting with steel. I became sensitive to its presence everywhere. I saw it in the tip of the ballpoint pen I was using to fill out the police form; it jangled on my dad’s key ring while he waited, fidgeting; later that day it sheltered and took me home, covering the outside of our car in a layer no thicker than a postcard. When we got home I sat down next to my parents at the kitchen table, and we ate soup together in silence. I even had a piece of steel in my mouth. Why didn’t it taste of anything?

There is something almost Ballardian about the connections Miodownik draws between materials and violence (car accidents, improvised weapons) and, of course, culture:

Comments closedThe fundamental importance of materials is apparent from the names we have used for stages of civilisation – the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age. Steel was the defining material of the Victorian era, allowing engineers to create suspension bridges, railways, steam engines and passenger liners. The 20th century is often hailed as the Age of Silicon, after the breakthrough in materials science that ushered in the silicon chip and the information revolution. Yet this is to overlook the array of other new materials that revolutionised modern living.

Architects took mass-produced sheet glass and combined it with structural steel to produce skyscrapers that invented a new city life. Product and fashion designers adopted plastics and transformed our homes and dress. Polymers were used to produce celluloid and brought about the biggest change in visual culture for 1,000 years, the cinema. The development of aluminium alloys and nickel superalloys enabled us to build jet engines and fly cheaply, thus accelerating the collision of cultures. Medical and dental ceramics allowed us to rebuild ourselves and redefine disability and ageing.

In this new RSA Animate, Manuel Lima, senior UX design lead at Microsoft Bing and author of Visual Complexity, talks about networks and the challenges of mapping a complex world:

Comments closedInspired by Brian Christian’s new book The Most Human Human, the chaps from Radiolab examine what talking to machines can tell us about being human. The show includes an interview with Jon Ronson, author of The Pyschopath Test, about an article he wrote for GQ on talking to robots.

Brian Christian was also interviewed about The Most Human Human recently by CBC Radio’s technology and culture show Spark.

Comments closedVisual Vocabulary — An interesting interview with book designer Peter Mendelsund at Czech Position:

I definitely take into account the author’s native culture, though whether I choose to adopt something stylistic from this culture depends on the vagaries of the particular project. There are times when one wants to accentuate the universal aspects of a writer’s work; and there are times when one wants to situate an author in a specific time and place… With Kafka, I would argue that his greatness lies in the universality of his ideas, that his writing transcends time and place… Conversely, with many other writers, nationality is at the core of their work — their great subject is place and contextual identity. They may write about Czech-ness, or English-ness, etc. These are the books where it makes the most sense to bring the local artistic tropes and visual cues to bear. For what it’s worth, I love delving into the visual vocabulary of different cultures.

The Casual Optimist interview with Peter is here, and you can read my 2-cents on his Kafka redesigns here.

The Polish Club — 50 Watts asks you to design the Polish edition of your favourite book. $400 is up for grabs.

Living by Dying — Ben Ehrenreich, author of The Suitors and Ether (forthcoming), on the death of the book in the new Los Angeles Review of Books:

For the record, my own loyalties are uncomplicated. I adore few humans more than I love books. I make no promises, but I do not expect to purchase a Kindle or a Nook or any of their offspring. I hope to keep bringing home bound paper books until my shelves snap from their weight, until there is no room in my apartment for a bed or a couch or another human being, until the floorboards collapse and my eyes blur to dim. But the book, bless it, is not a simple thing… [W]hat could it mean for the book to die? Which sort of book? And what variety of death? What if the book had only ever lived by dying?

A World Made of Stories — James Gleick, author of The Information, on memes:

In the competition for space in our brains and in the culture, the effective combatants are the messages. The new, oblique, looping views of genes and memes have enriched us. They give us paradoxes to write on Möbius strips. “The human world is made of stories, not people,” writes the novelist David Mitchell. “The people the stories use to tell themselves are not to be blamed.” Margaret Atwood writes: “As with all knowledge, once you knew it, you couldn’t imagine how it was that you hadn’t known it before. Like stage magic, knowledge before you knew it took place before your very eyes, but you were looking elsewhere.” Nearing death, John Updike reflected on

A life poured into words—apparent waste intended to preserve the thing consumed.

Fred Dretske, a philosopher of mind and knowledge, wrote in 1981: “In the beginning there was information. The word came later.” He added this explanation: “The transition was achieved by the development of organisms with the capacity for selectively exploiting this information in order to survive and perpetuate their kind.” Now we might add, thanks to Dawkins, that the transition was achieved by the information itself, surviving and perpetuating its kind and selectively exploiting organisms.

Cull or be Culled — NPR’s Linda Holmes on how we are missing everything:

You used to have a limited number of reasonably practical choices presented to you, based on what bookstores carried, what your local newspaper reviewed, or what you heard on the radio, or what was taught in college by a particular English department. There was a huge amount of selection that took place above the consumer level. (And here, I don’t mean “consumer” in the crass sense of consumerism, but in the sense of one who devours, as you do a book or a film you love.)

Now, everything gets dropped into our laps, and there are really only two responses if you want to feel like you’re well-read, or well-versed in music, or whatever the case may be: culling and surrender.

And on a related note…

Lester Bangs’ Basement — Bill Wyman on collecting and scarcity at Slate:

Lester Bangs, the late, great early-rock critic, once said he dreamed of having a basement with every album ever released in it… [T]he Internet today is very much like [that]. In its vastness, cacophony, and inaccuracy, it’s also very reminiscent of Borges’ Library of Babel. Just as that library contained books made up of every possible combination of letters, in the corners of the Internet I’m concerned with here you can find similar chaos: The song “Let It Be” by the Beatles, sure, but also mislabeled as by the Stones, by the Kinks, by the Hollies, by the “Battles” … and also with, of course, those same labels attached to entirely different songs (like “Let It Bleed”).

Anyway, is it enough?

For some, the enjoyment of art or culture has fetishistic aspects. To them, being a fan is about something more than just experiencing the art. There will always be collectors, fixating on the physical objects, like the great LP jackets from the 1960s and 1970s… And there will always be people who can’t be happy unless they have something regular fans don’t. Indeed, a friend of Bangs’, long after he died, said to me that the unspoken corollary in Bangs’ mind to his fantasy was that no one else would have access to it.

Happy Easter.

Comments closedWNYC’s Radiolab searches for order and balance in the world around us, and asks how symmetry shapes our existence — from the origins of the universe, to what we see when we look in the mirror:

RADIOLAB: Desperately Seeking Symmetry

The episode is accompanied by this lovely video by Everynone:

2 CommentsTim Minchin’s 9-minute beat poem Storm — a witty and f-bomb fuelled defense of science and critical thinking — is beautifully delivered in this animated movie directed by DC Turner and produced by Tracy King:

(via Quipsologies)

Comments closedIn a really fascinating 28 minute interview from last year, Louis Menand — Professor of English at Harvard University, critic and author most recently of The Marketplace of Ideas — discusses books, culture, criticism, science, education (and more in between) with the Big Think:

(via Mark Athitakis. I can’t quite believe I didn’t see this earlier!)

Comments closed