Dan Chiasson takes a look at the making (and meaning) of Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ for The New Yorker:

Kubrick brought to his vision of the future the studiousness you would expect from a history film. “2001” is, in part, a fastidious period piece about a period that had yet to happen. Kubrick had seen exhibits at the 1964 World’s Fair, and pored over a magazine article titled “Home of the Future.” The lead production designer on the film, Tony Masters, noticed that the world of “2001” eventually became a distinct time and place, with the kind of coherent aesthetic that would merit a sweeping historical label, like “Georgian” or “Victorian.” “We designed a way to live,” he recalled, “down to the last knife and fork.” (The Arne Jacobsen flatware, designed in 1957, was made famous by its use in the film, and is still in production.) By rendering a not-too-distant future, Kubrick set himself up for a test: thirty-three years later, his audiences would still be around to grade his predictions. Part of his genius was that he understood how to rig the results. Many elements from his set designs were contributions from major brands—Whirlpool, Macy’s, DuPont, Parker Pens, Nikon—which quickly cashed in on their big-screen exposure. If 2001 the year looked like “2001” the movie, it was partly because the film’s imaginary design trends were made real.

Much of the film’s luxe vision of space travel was overambitious. In 1998, ahead of the launch of the International Space Station, the Times reported that the habitation module was “far cruder than the most pessimistic prognosticator could have imagined in 1968.” But the film’s look was a big hit on Earth. Olivier Mourgue’s red upholstered Djinn chairs, used on the “2001” set, became a design icon, and the high-end lofts and hotel lobbies of the year 2001 bent distinctly toward the aesthetic of Kubrick’s imagined space station.

I have to confess that I’m with Renata Adler — I’ve always found 2001 to be simultaneously “hypnotic and immensely boring.” I think I just like reading about Kubrick’s films far more than I actually like watching them.

Chiasson’s essay reminded me Keith Phipps great series on science fiction films ‘The Laser Age’ for late and lamented film website The Dissolve, which started with 2001. Someone really should collect those essays together into a book if they haven’t already,

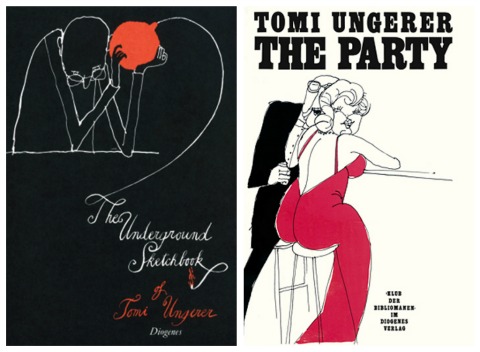

The cover of Michael Benson’s book on the making of 2001, Space Odyssey, was designed by Rodrigo Corral and was featured in this month’s book covers post.

Comments closed