As mentioned earlier, I was in Vancouver last week and I wasn’t able to post as regularly as I would have liked to. So to make up for Friday’s missing links, here are a few things of interest to start the week off…

Adrian Tomine (Shortcomings) discusses his latest work, Optic Nerve #12, and an unfinished graphic novel with Comic Book Resources:

Adrian Tomine (Shortcomings) discusses his latest work, Optic Nerve #12, and an unfinished graphic novel with Comic Book Resources:

When I finally sat down to work on my next comics project, I felt obligated to attempt a real “graphic novel.” I was looking at these giant tomes that some of my peers were working on, and I felt really envious of that kind of achievement. It also just seemed like that was the direction everything was moving in, and my old habit of publishing short stories in the comic book format was already an anachronism. So I pursued that for awhile, doing a lot of the kind of preparatory work which is actually the hardest part for me, and the whole time I had these nagging thoughts like, “Do I really want to work on this for ten years? Do I want to draw and write in the same way for that long? Does the material really merit that much of an investment?”

Hard Won — Yet another review for MetaMaus in The New York Times:

Spiegelman recalls the struggles of researching “Maus” at a time before scholarship was widely available to a mass audience. Pre-Internet, he depended on his parents’ collection of pamphlets written and drawn by survivors, and on research visits to Poland. On his second trip to Birkenau, in 1987, Spiegelman was baffled to find a perfectly preserved barracks where once there had been only rubble; it turned out to be a re-creation built for a Holocaust movie, left standing by Polish authorities because it looked accurate. He admits he was jealous of the moviemakers’ unlimited resources, when “every scrap of information I needed for ‘Maus’ was so hard-won.”

With It — Michael Farr, author of Tintin: The Complete Companion, talks about Tintin and discusses five books related to Herge and his creation at The Browser:

If you didn’t meet Hergé, you wouldn’t realise how funny he was – he saw the humorous side of almost everything. He was visually terribly aware, he didn’t miss anything which he saw. He was in his seventies then and I was in my mid-twenties, and I think that’s the reason why he agreed to see me. Younger, a French-speaking British journalist, I was slightly exotic and that intrigued him. Hergé was terribly young for his age. To use an expression that was used more then than now, he was very “with it”. When we got talking about music, he asked me what my favourite Pink Floyd songs were.

You see all this in the books. In many respects, Hergé is Tintin himself.

See also: Hal Foster, art critic and author of The First Pop Age (i.e. not THAT Hal Foster), on pop art at The Browser.

And finally…

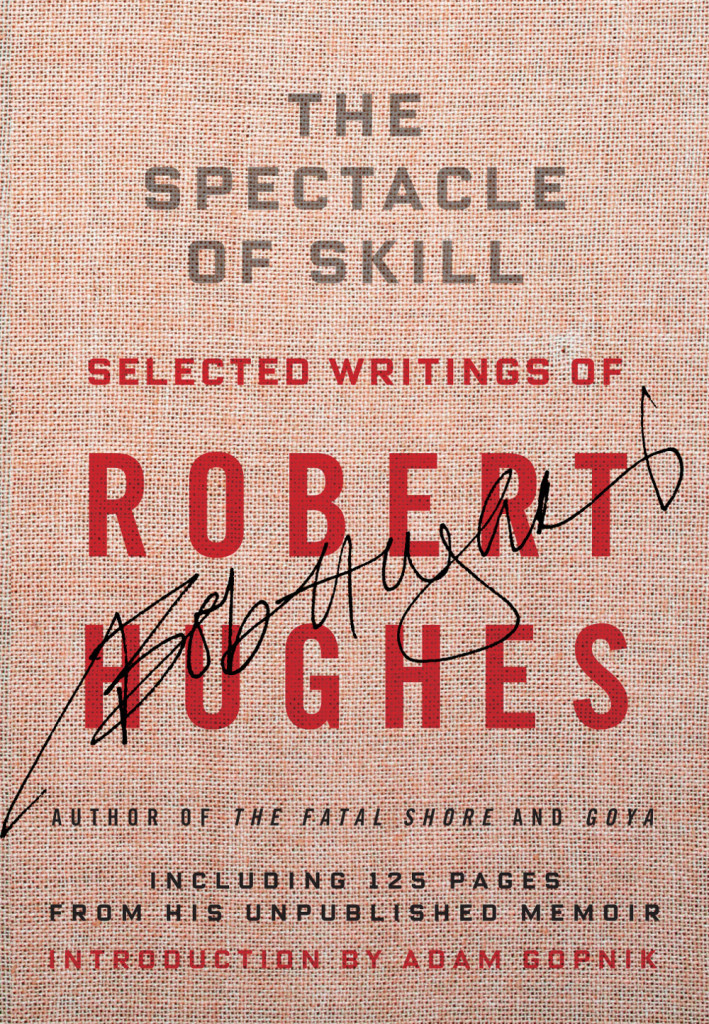

Art critic Robert Hughes on his first visit to Rome, excerpted from his new book about the city, in The WSJ:

It was being gradually borne in on me by Rome that one of the vital things that make a great city great is not mere raw size, but the amount of care, detail, observation and love precipitated in its contents, including, but not only, its buildings. And it goes without saying, or ought to, that one cannot pay that kind of attention to detail until one understands quite a bit about substance, about different stones, different metals, the variety of woods and other substances—ceramic, glass, brick, plaster and the rest—that go to make up the innards and outer skin of a building, how they age, how they wear: in sum, how they live, if they do live.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Adrian Tomine (

Adrian Tomine (