The Betamax of Printing — A lovely post on medieval block books posted at The Catologuer’s Desk:

Block books were a sideline in the world of early printing, appearing concurrently with Gutenberg’s invention in the 1450s and 60s. Movable type and the printing press had their origins in metalworking and wine pressing. Block books, on the other hand, developed from the use of wood engravings to cheaply and quickly print fabrics, devotional items, and playing cards. Each block book was composed of individual prints that were produced by rubbing a wood engraving against paper, and they were often hand-coloured. What little text was included was usually incorporated directly into the engraving, a delicate and time-consuming process, but worthwhile because the prints could be mass produced without the capital outlay required for type.

(Is that actually a relevant, non-spurious mention of Gutenberg in a post about books and publishing? That must be a first!)

Drowning in an Ocean of Slush — Laura Miller on reading when everyone can publish for Salon:

What’s most striking… about the many, many conversations I’ve had about e-books, innovations in self-publishing and the emergence of publicity venues like social networking is how difficult it is to stayed focused on what all of this means for readers. No matter how hard you try, within five minutes the talk turns inexorably back to how agents, editors and publishers will suffer in the coming cataclysmic change — and, above all, how gloriously liberating it will be for authors… How readers feel about all this usually gets lost in the fanfare and the hand-wringing… Readers themselves rarely complain that there isn’t enough of a selection on Amazon or in their local superstore; they’re more likely to ask for help in narrowing down their choices. So for anyone who has, however briefly, played that reviled gatekeeper role, a darker question arises: What happens once the self-publishing revolution really gets going…?

You and Sonny Mehta — Another reminder from Clay Shirky, author of Here Comes Everybody and Cognitive Surplus (and who is sounding terribly pleased with himself these days), that we are all fucked:

The interesting clash to me is between you and say, Sonny Mehta… You’re both in the same industry, but from his point of view if he can just hold it together 10 more years, he’s fine. He can retire. But you know that if you stay in the book industry 30 more years, there’s no way that things will be anything like today. Sonny Mehta’s incentive is to postpone—even if it makes things worse—the moment of shock to right after he retires. But you don’t have that option. I’m interested in young writers and editors entering a system that is plainly structured around the vestiges of a world fast draining away.

Meanwhile, from the other end of the spectrum…

…Distracted — An interview with Nicholas Carr, who has followed up his essay ‘Is Google Making Us Stupid?’ with The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, at Open Culture:

The Web is now about 20 years old. Up until recently, we’ve been dazzled by its riches and conveniences – for good reason. Now, though, I think we’re becoming more aware of the costs that go along with the benefits, of what we lose when we spend so much time staring into screens. I sense that people, or at least some people, are beginning to sense the limits of online life. They’re craving to be more in control of their attention and their time.

Nicholas Carr also discusses his new book with Norah Young on this week’s Spark on CBC Radio.

And finally (just in case you’re wondering)…

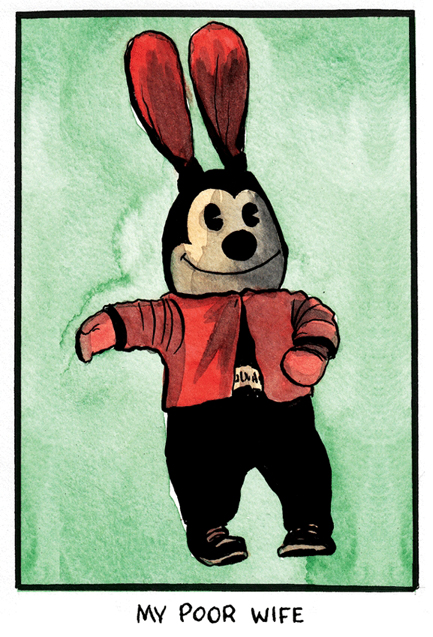

Here’s the latest from cartoonist James Sturm on life without the internet at Slate:

In the two months since I’ve been unplugged, I have been experiencing more and more moments of synchronicity—coincidental events that seem to be meaningfully related. Today, after finishing the first phase of a graphic-novel project that is based on the life of a fictional member of the Weather Underground, I received in the mail an unsolicited copy of a graphic novel about teaching written by William Ayers. Earlier in the week, at the exact moment I started working on a drawing of a monkey (see above), Michael Chabon started talking about Planet of the Apes… I know this type of magical thinking is easily dismissed, but I keep having moments like this. So how do I explain it? Are meaningful connections easier to recognize when the fog of the Internet is lifted? Does it have to do with the difference between searching and waiting? Searching (which is what you do a lot of online) seems like an act of individual will. When things come to you while you’re waiting it feels more like fate. Instant gratification feels unearned. That random song, perfectly attuned to your mood, seems more profound when heard on a car radio than if you had called up the same tune via YouTube.

http://www.bookdepository.co.uk/book/9780393072228/?a_aid=optimist

Like this:

Like Loading...