Rubbish — Rachel Cooke on the artist Kurt Schwitters at The Guardian:

Merz doesn’t mean anything: it is a nonsense word (it comes from Commerzbank, an ad for which appears in one of his earliest collages). But after 1918 everything Schwitters made was Merz, whether it was periodical, painting or poem. He was a one-man movement. “The word denotes essentially the combination of all conceivable materials for artistic purposes,” he said. “And technically the principle of equal evaluation of the individual materials… A perambulator wheel, wire-netting, string and cotton wool are factors having equal rights with paint.” In other words, art could be made from the things most people regarded as rubbish. Almost overnight, he became a collagist.

There is a slide-show of Schwitters’ collages here.

Also: Merzman: The Art of Kurt Schwitters, is a fascinating 30-minute BBC Radio 4 documentary about the artist and his work in Britain.

The exhibition Kurt Schwitters in Britain opens at the Tate January 30, 2013.

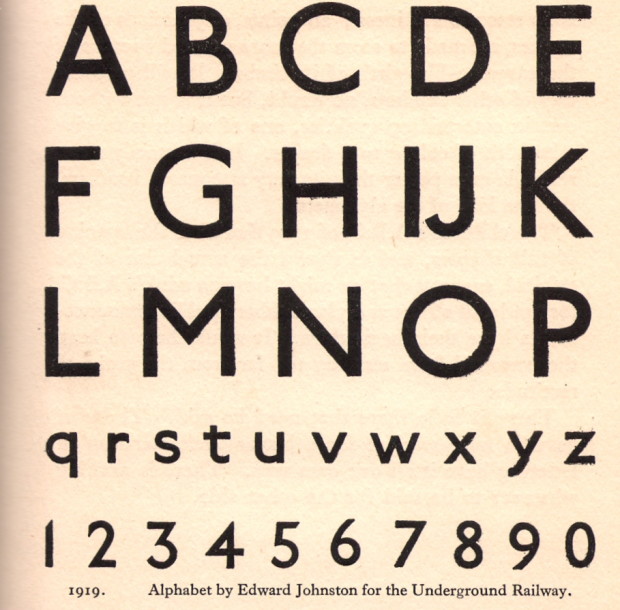

Going Underground — The iconic London Underground typeface, designed by Edward Johnston in 1913, turns 100:

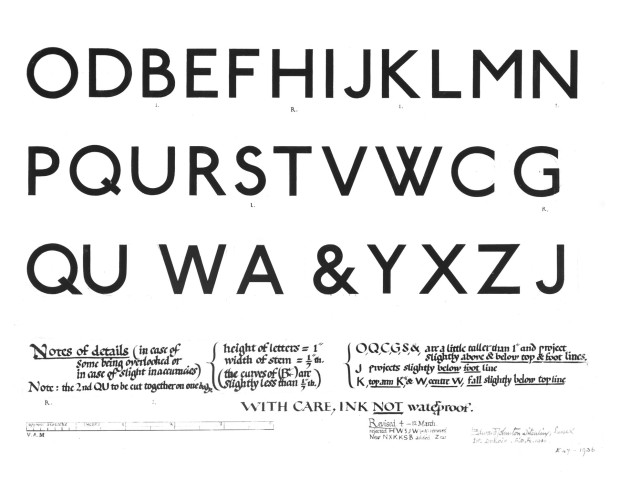

“Underground” — later known as “Johnston” — was circulated as a lettering guide for sign-painters and also made into wood and metal type for posters, signs, and other publicity materials used throughout London’s transport network.

Johnston himself only drew one weight of the typeface. He based its weight and proportions on seven diamond-shaped strokes of a pen stacked in a row. This gesture even shows up in the typeface itself, with the characteristic diamond used as the tittle of the “i” and “j”. He felt so strongly about the weight of the design that when another student of his agreed to create an accompanying set of bold capitals, Johnston wouldn’t speak to him for decades afterward.

And finally…

Fire Hose — James Gleick on the Library of Congress collecting and storage of Twitter messages, for the New York Review of Books:

This is an ocean of ephemera. A library of Babel. No one is under any illusions about the likely quality—seriousness, veracity, originality, wisdom—of any one tweet. The library will take the bad with the good: the rumors and lies, the prattle, puns, hoots, jeers, bluster, invective, bawdy probes, vile gossip, epigrams, anagrams, quips and jibes, hearsay and tittle-tattle, pleading, chicanery, jabbering, quibbling, block writing and ASCII art, self-promotion and humblebragging, grandiloquence and stultiloquence. New news every millisecond. A vast confusion of vows, wishes, actions, edicts, petitions, lawsuits, pleas, laws, proclamations, complaints, grievances. Now comical then tragical matters.

Call it what you will, the Twitter corpus now forms a piece of “the creative record of America” and therefore falls squarely within the library’s mission…

Like this:

Like Loading...