An unforeseen consequence of the “New Think for Old Publishers” debacle at SXSW in earlier this year is that I will be a participant in a session on the role of the publishers in the digital age at Book Camp Toronto on June 6th.

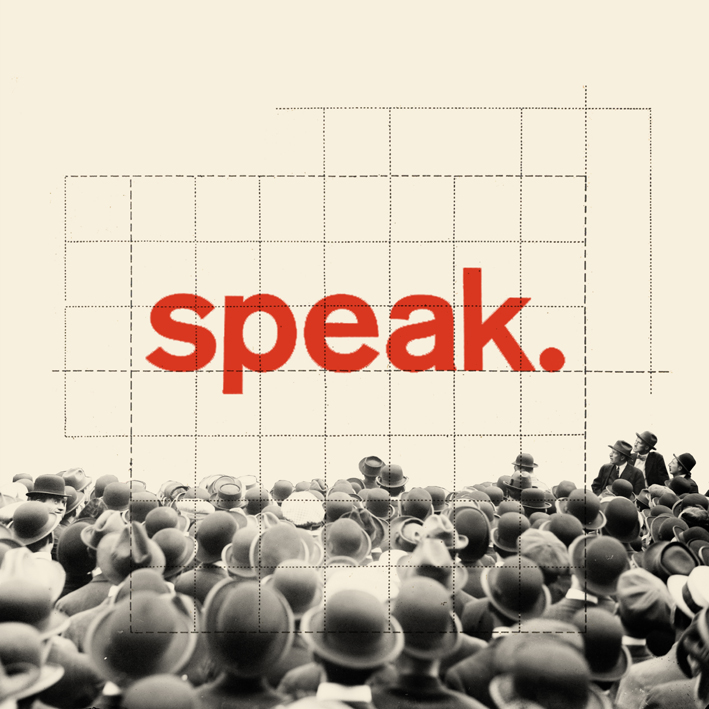

140 Character Assassination

The now infamous SXSW panel was supposed to discuss “what’s going right and what’s going wrong in publishing, assess success of recent forays into marketing digitally, digital publishing, and what books and blogs have to gain from one another.”

As has been well documented elsewhere, things did not go according to plan.

Despite the presence of heavyweight panelists (including the venerable Clay Shirky), new ideas were in short supply. Audience frustration overflowed on to Twitter and an array of 140 character bullets (identified by a #sxswbp hashtag) ripped into the panel, with what was perhaps the kill-shot fired by a writer in the audience:

“If, as an author, I can design it myself, write it myself, publish it myself, why would I bother going to a publisher at all? What purpose do you serve?”*

Existential Crisis

The old answer to this question was that publishers offered technical expertise and mass distribution.

But, nowadays, digital technology has made it easy for writers to publish, distribute and market their own books independently. And whilst professional editing, design, production, distribution, and marketing may still be valuable and sought-after services, it’s become very apparent that the perceived gap between self-publishing and traditional publishing is narrowing.

The battering that the SXSW panel took inadvertently revealed what we have long-suspected — publishers need to change the way they think about themselves, the decisions they make, and the services they offer, or cease to exist.

Fine Filtering

One idea that gained some currency in the aftermath of SXSW was that publishers are — or could be — ‘cultural curators’, a role made only more important by the explosion of content created and distributed by digital technology.

In a world where it is impossible to read everything that is emailed, texted, tweeted, posted, uploaded, or printed, there is an opportunity for publishers to become trusted advisers who sift through the vast digital slush-pile and present only the best, most interesting work. Or so the argument goes.

Unfortunately, the truth of the matter is that publishers haven’t proved to be very effective at curating in the past, and it’s precisely this kind of pretension that gets them in trouble at events like SXSW.

A rap sheet of opportunistic publishing, self-indulgence, costly blunders, and generally too much poor product means that publishers (not to mention the mainstream media) have squandered any cultural authority they may once have had, and have been superseded by an informal network of curators connected online.

Furthermore, curation doesn’t really explain what publishers actually do for authors. If it’s just filtering (by set a of cultural criteria I may or may not agree with), why bother going to a publisher at all?

Strengthening the Signal

Not long after after SXSW I sat down in Toronto with Book Camp TO organizer Hugh McGuire to discuss these crumbling cultural hierarchies and the implications for publishers.

Expressing my dissatisfaction with the idea of publishers as curators — and trying to take into account Hugh’s reader-centric approach — I suggested that perhaps we’d stand ourselves in better stead if we thought of ourselves more as ‘advocates’.

More proactive than curation, advocacy takes into account that publishers do more than find completed works of art and present them to the public. And it goes at least part way towards explaining what publishers do for authors, whilst offering a model for how they can interact meaningfully (and honestly) with readers.

Perhaps, just as crucially, it also means being able to effectively publish and promote books that we believe in, without making any of the claims of cultural authority or superiority that are attached to curating — the framework of advocacy works whether you are publishing literary fiction or genre, poetry or humour.

Admittedly, there are probably minimal and maximal versions of what ‘publisher as advocate’ means. On the minimal side, publishers promote (and defend if necessary) their books in the public forum. A more maximal version — which is probably where my thinking lies — would not simply limit advocacy to marketing a finished product. It would begin with the commissioning editor championing the work in-house, and continue through the production of the book to the publicist who is pitching it to reviewers, and beyond. It would also mean publishing less and publishing better.

So…

These ideas are not definitive. In fact they’re a rather hurried formation (at the prompting of Sean Cranbury) of a jumble of ideas that I’ve had kicking around my head that need more time, but also more air and more discussion.

The Book Camp Toronto session about the role of publishers is on Saturday June 6th at the University of Toronto’s iSchool. Please come along and share your ideas. If you can’t make it, please feel free to leave your feedback, ideas, and links in the comments section or send me an email or a DM.

Over and Out.

* For the record, this quotation is from panelist Peter Miller‘s account of #sxswbp

Like this:

Like Loading...