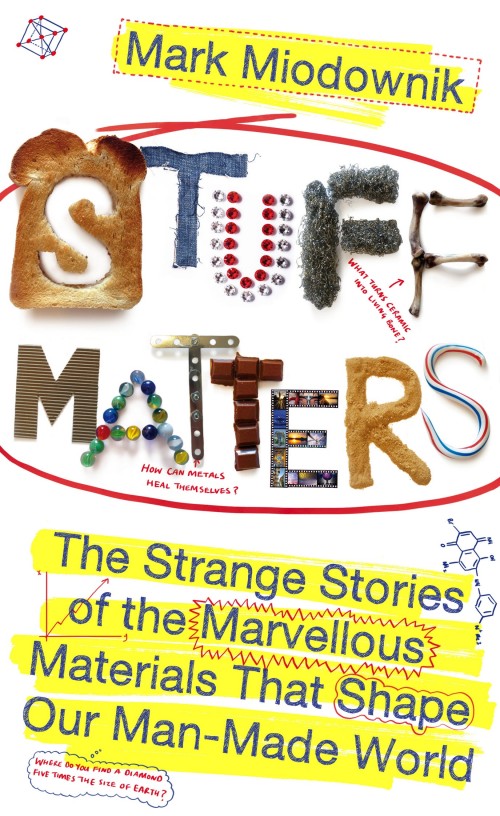

In what is presumably an excerpt from his new book Stuff Matters, materials scientist and engineer Mark Miodownik describes how his obsession with materials began with being attacked on the London Underground:

I was right about one thing: he didn’t have a knife. His weapon was a razor blade wrapped in tape. This tiny piece of steel, not much bigger than a postage stamp, had easily cut through five layers of my clothes, and then through the epidermis and dermis of my back in one swipe. When I saw the weapon in the police station later, I was mesmerised. As the police quizzed me, the table between us wobbled and the blade sitting on it wobbled too. In doing so it glinted in the fluorescent lights, and I saw that its steel edge was still perfect, unaffected by its afternoon’s work.

This was the birth of my obsession with materials – starting with steel. I became sensitive to its presence everywhere. I saw it in the tip of the ballpoint pen I was using to fill out the police form; it jangled on my dad’s key ring while he waited, fidgeting; later that day it sheltered and took me home, covering the outside of our car in a layer no thicker than a postcard. When we got home I sat down next to my parents at the kitchen table, and we ate soup together in silence. I even had a piece of steel in my mouth. Why didn’t it taste of anything?

There is something almost Ballardian about the connections Miodownik draws between materials and violence (car accidents, improvised weapons) and, of course, culture:

The fundamental importance of materials is apparent from the names we have used for stages of civilisation – the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age. Steel was the defining material of the Victorian era, allowing engineers to create suspension bridges, railways, steam engines and passenger liners. The 20th century is often hailed as the Age of Silicon, after the breakthrough in materials science that ushered in the silicon chip and the information revolution. Yet this is to overlook the array of other new materials that revolutionised modern living.

Architects took mass-produced sheet glass and combined it with structural steel to produce skyscrapers that invented a new city life. Product and fashion designers adopted plastics and transformed our homes and dress. Polymers were used to produce celluloid and brought about the biggest change in visual culture for 1,000 years, the cinema. The development of aluminium alloys and nickel superalloys enabled us to build jet engines and fly cheaply, thus accelerating the collision of cultures. Medical and dental ceramics allowed us to rebuild ourselves and redefine disability and ageing.